Peter Kleinmann

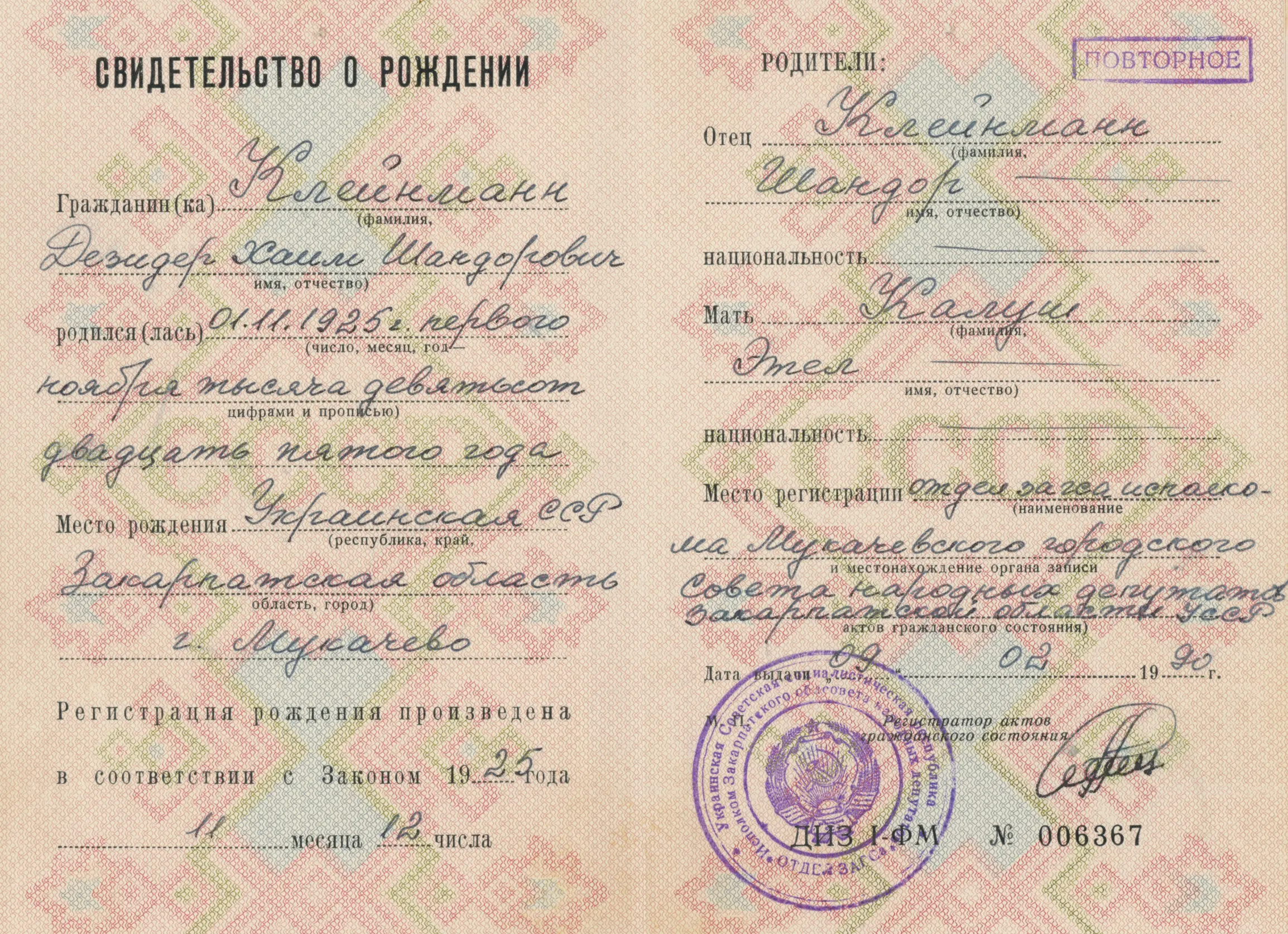

Peter was born as Dezider Kleinmann on 31 October 1925 in Kuštanovice, a small village near the city of Munkács in Czechoslovakia. His Hebrew names were Dovid and Wolfe but his family and friends called him Dudi. He grew up in Kuštanovice and Munkács.

On 18 April 1944, Peter and his family had to move into the Ghetto which was established in the Jewish section of the city of Munkács. Conditions in the Ghetto were difficult. 16 people shared four rooms and food was scarce.

After a few weeks in the Ghetto, the Kleinmann family was deported on 22 May 1944. Herded into cattle cars they travelled for two nights and three days with nearly no food or water. They were brought to Auschwitz, where Dezider was separated from his family.

After a few days he was put on a cattle car again and brought to the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. For the first three or four weeks Dezider had to work in the quarry for eight to ten hours a day. Work in the quarry was deadly. Dezider had already begun to lose weight and strength when one day he was assigned to work in the Messerschmidt factory which was easier work indoors.

In fall 1944, he was sent with thousands of other prisoners on a death march. For about six weeks they had to walk for several hours a day.

The death march brought Dezider to the Flossenbürg concentration camp. There he first had to work in another Messerschmidt factory. In November he was taken away from the factory to work on the railroad and after a few weeks he was transferred to the quarry. Besides the omnipresent hunger these tasks meant physically exhausting work under intolerable weather conditions.

In February of 1945, after ten months as a concentration camp inmate Dezider was selected to be killed. Alongside other selected prisoners he was brought to a holding barrack where their numbers were recorded. Standing in front of the prisoner who noted the numbers he realized that this man was his brother Moishe Avrum. His brother managed to keep Dezider in the holding barrack without his number surfacing on the list of those sent from the barrack to the killing centres. The day before the inmates of the camp were sent on a death march Moishe Avrum brought Dezider with him to the typhus ward which would not be evacuated. This way they were both liberated in Flossenbürg.

Dezider Kleinmann received the name Peter in Flossenbürg after liberation. One of the American officers who had a hard time pronouncing Dezider gave him his new name Peter.

Peter and his brother stayed in the liberated camp until August 1945, when they were given a farm in Ostionoff by the Czech government.

During spring 1946, Peter was diagnosed with tuberculosis and in fall he left Czechoslovakia for a sanatorium in Switzerland. He spent the next two years living in the Schatzalp Sanatorium near Davos.

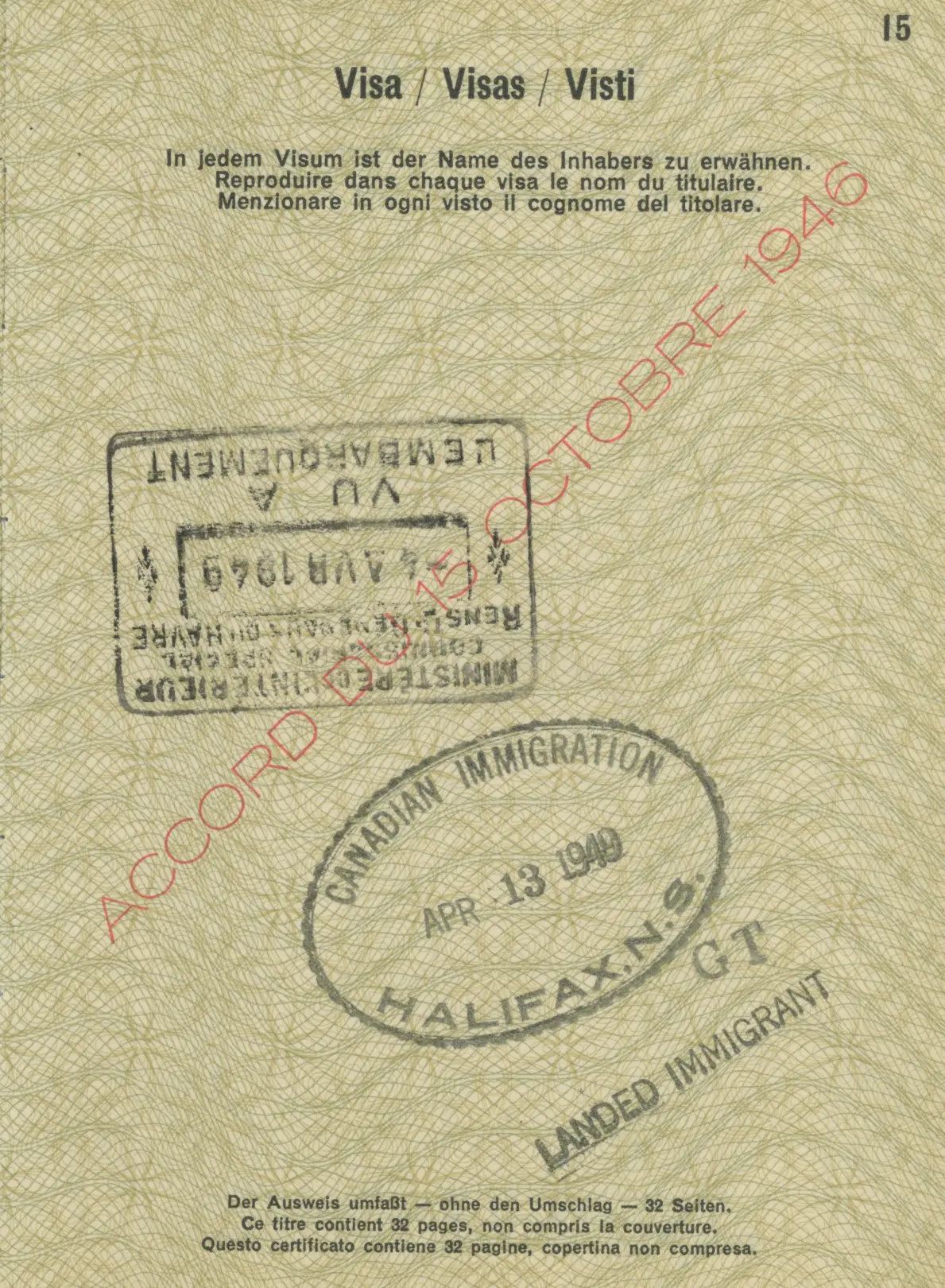

In the meantime, his brother had met a woman who had relatives in Canada. So, he decided to emigrate to Canada and Peter decided to come with him. From Switzerland Peter travelled to the French port of Le Havre and from there by boat to Halifax. He arrived there on 13 April 1949 and immediately travelled to Montreal by train where he met his brother and started his new life.

Documents

Peter Kleinmann’s immediate family members in prewar Munkács. Peter, Zsenka, Bumi, and Piri (from left to right) are standing in the back. Esther, Sandor, and Esther’s sister, Piri (from left to right) are seated in front of them.

Peter was the youngest of four children. His brother Moishe Avrum was called Bumi and his sisters were Piri and Zsenka. His father’s name was Alexander, but he was called Sandor and his mother was called Esther.

Peter and his siblings all survived the Shoah, their parents did not. Piri and Zsenka had remained in Auschwitz from the day the Kleinmann family had been separated on the infamous platform in May 1944, until they were sent on a death march a few days before the Red Army liberated the camp on 27 January 1945. They were among a group of approximately 1,000 women who were evacuated from the camp a few days before liberation. They marched for what fortunately was to be only a few days. At some point, they were abruptly stopped and without explanation made to board a train, to Bergen-Belsen. They remained there for the next few months until the Canadian and British armies liberated the camp on 15 April 1945.

Peter saw his parents for the last time during the separation of the family after the arrival in Auschwitz.

Zsenka and Joško Stern in prewar Munkács.

Joško Stern was Peter’s sister Zsenka’s boyfriend before the war. Both survived the Shoah. Joško’s story is a case in point. He had been forced into the Hungarian labour battalion in 1940. This battalion was captured on the front by the Russians in 1941 and sent to Siberia, where they joined the voluntary Czech and Slovak armies. These men intended to liberate their homelands and were in contact with the Czech government-in-exile. They marched for four years through Siberia and Russia to Munkács.

Through the Joint radio broadcasts, Zsenka discovered Joško. They met in Prague in May 1945, and returned to Munkács, where they were married on 21 September 1945. That evening they left for Liberec with Piri. There they operated a textile store where they made a good living selling scarce yard goods and buying American dollars. In 1950, they emigrated to New York with the help of Joško’s relatives.

Peter’s brother-in-law’s (David Spiegel) father, Emmanuel Menachem Mendel Spiegel, was born in 1888. He was an officer in the 65th regiment of the Austro-Hungarian Military and fought on the front from 1914 to 1918. Peter’s father, too, fought in the Austro-Hungarian army during the First World War.

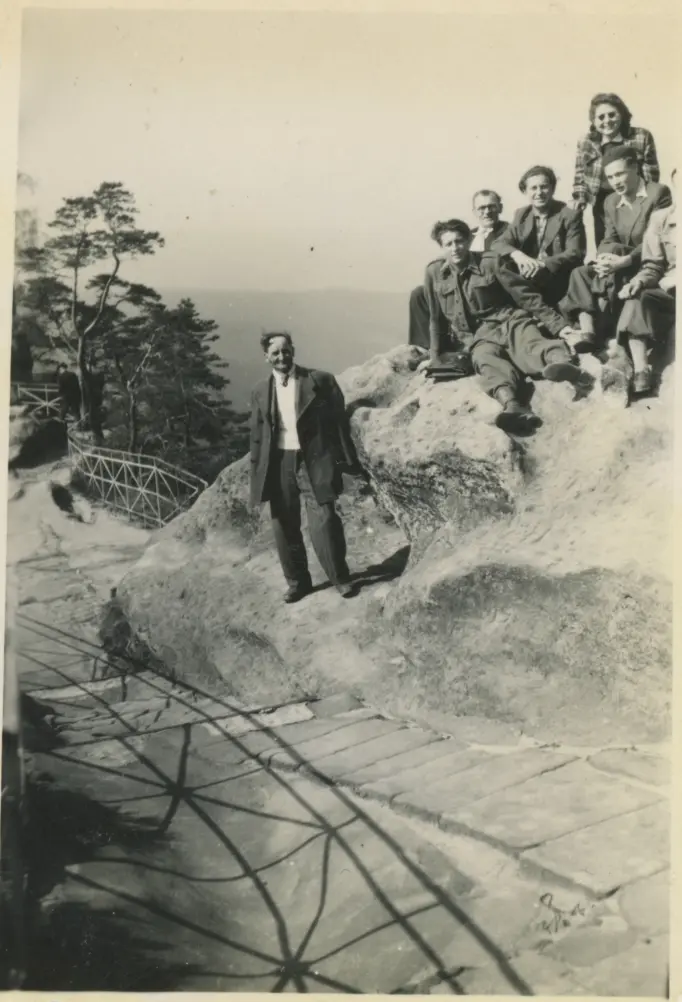

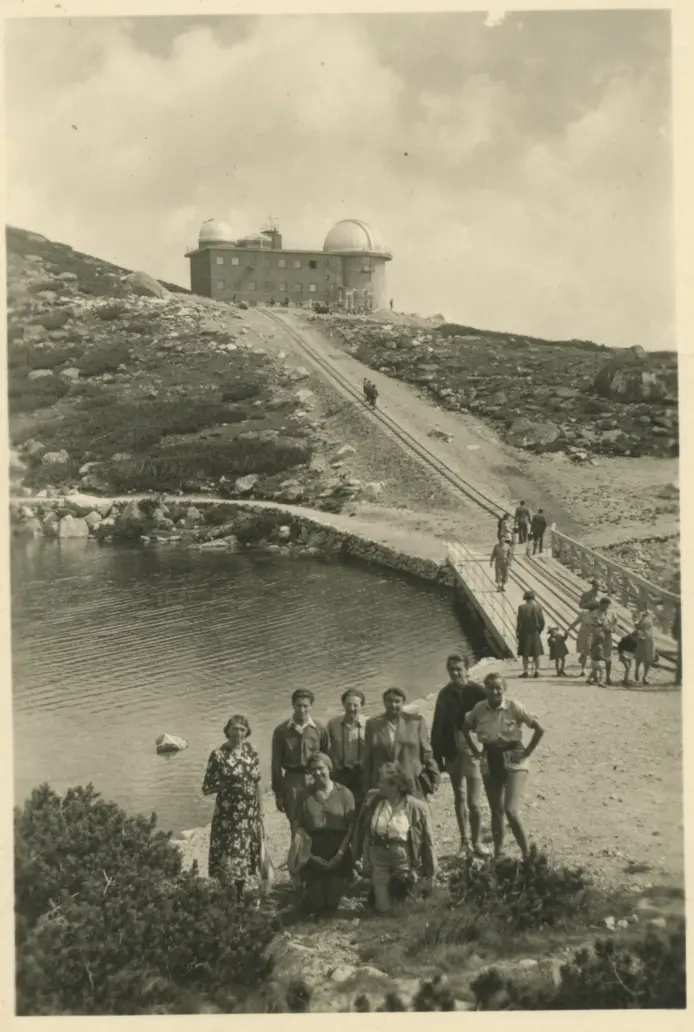

Peter and friends on Betar outings at Skalivati Pleso, 1942.

In 1942, Peter joined Betar, a Zionist organization that was composed of young men and women who were dedicated to establishing a state for the Jews. On Friday nights after his father was asleep, Peter slipped out of the house and went to the social gatherings. Peter proposed to his father that they go to Palestine, but he adamantly refused.

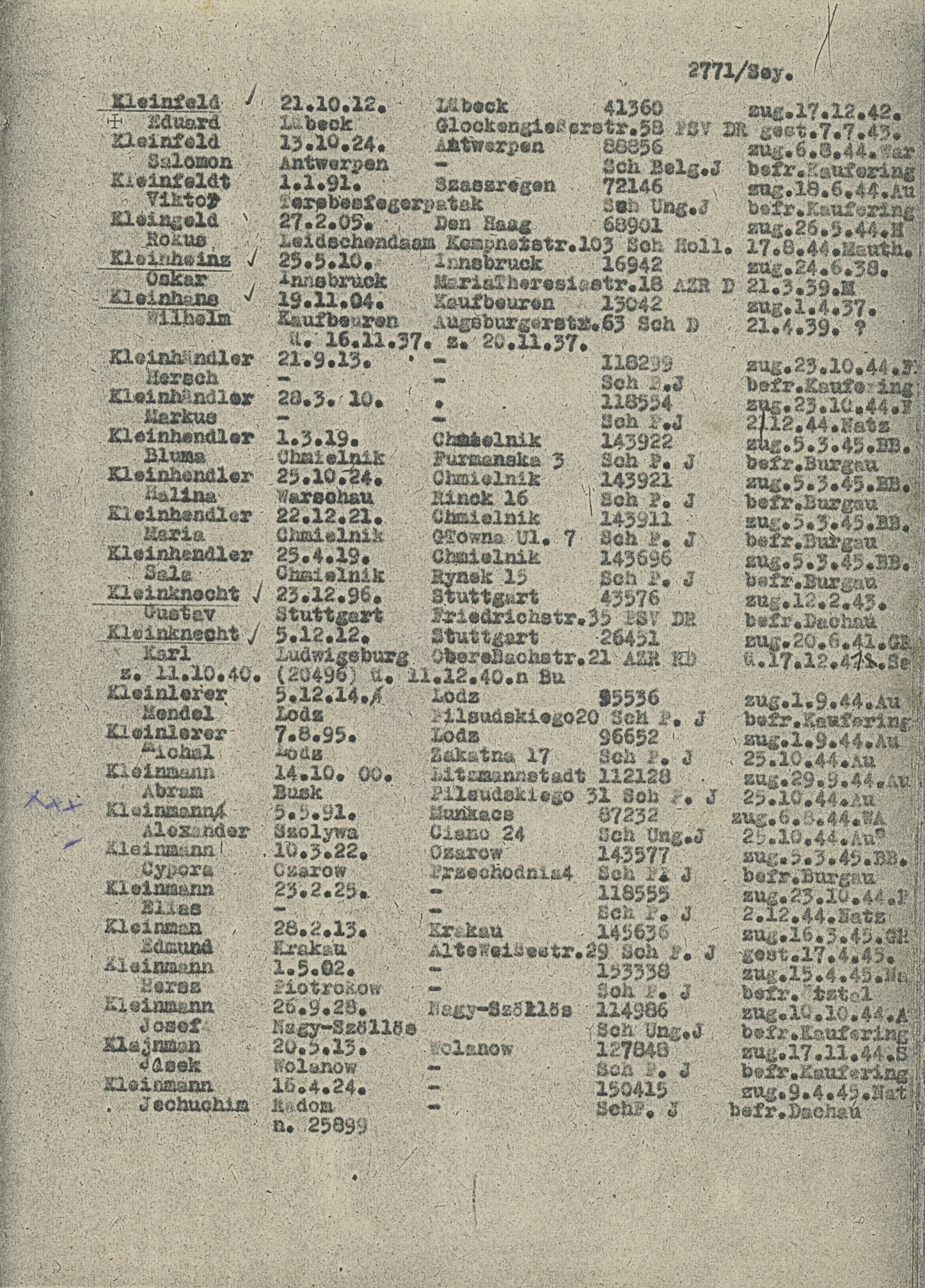

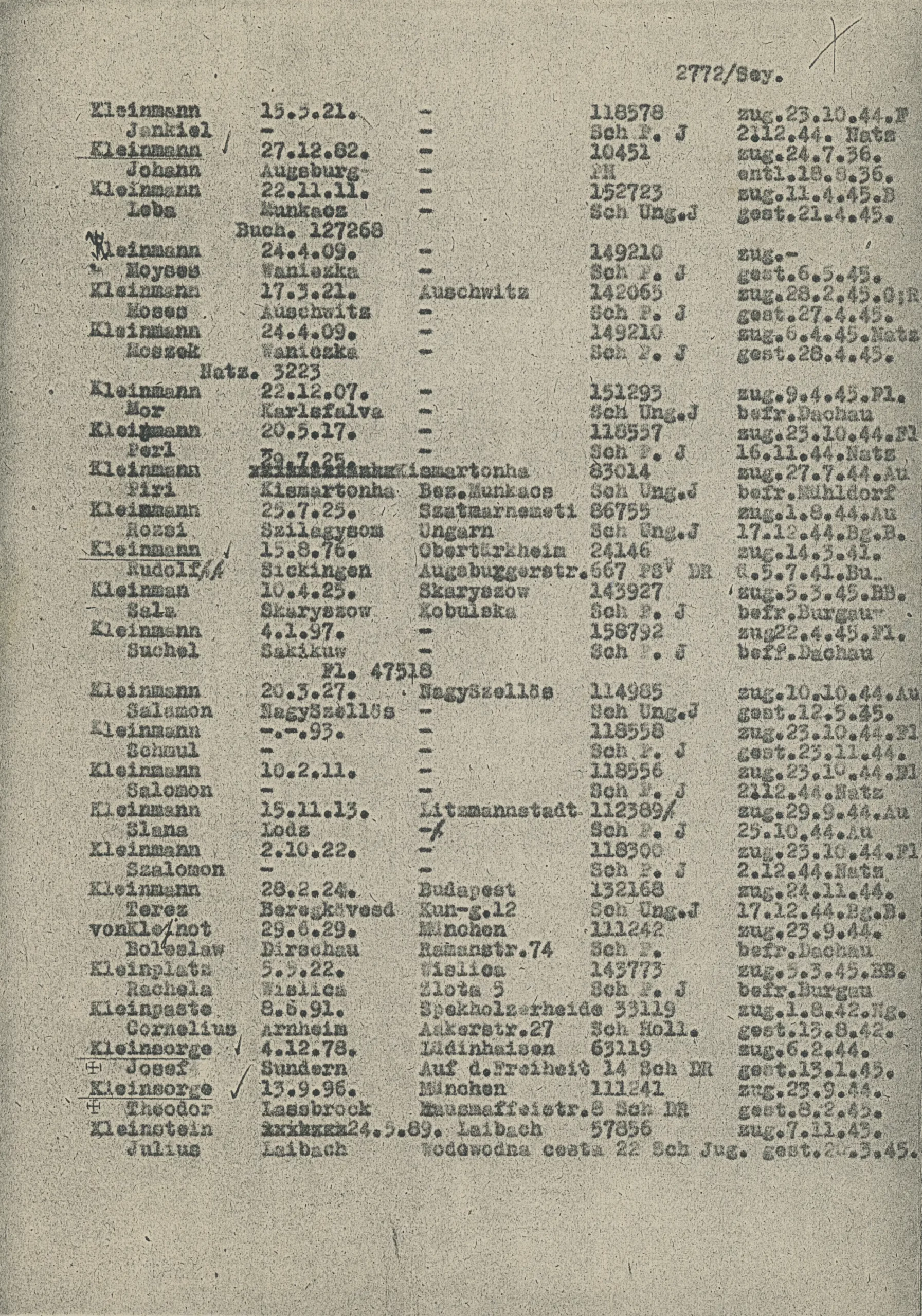

This is a copy of the document detailing Peter’s father’s journey from Auschwitz to his death in Dachau. Peter discovered this list at the Memorial site of Dachau in 1995. Dachau was the Nazis’ first concentration camp opened in 1933 and was closed only weeks after Sandor Kleinmann’s death in April 1945.

Peter is wearing an American military uniform in the former Flossenbürg concentration camp in May 1945.

Peter and his brother were given the uniforms by their American liberators. The former inmates were confined in the camp until they were issued identification papers and travel passes. Peter’s new name, Peter, was also adopted during this time after the liberation in Flossenbürg. One of the American officers who had a difficult time pronouncing Dezider said to him, “You look like a Peter.” So, he has been known as Peter since 1946.

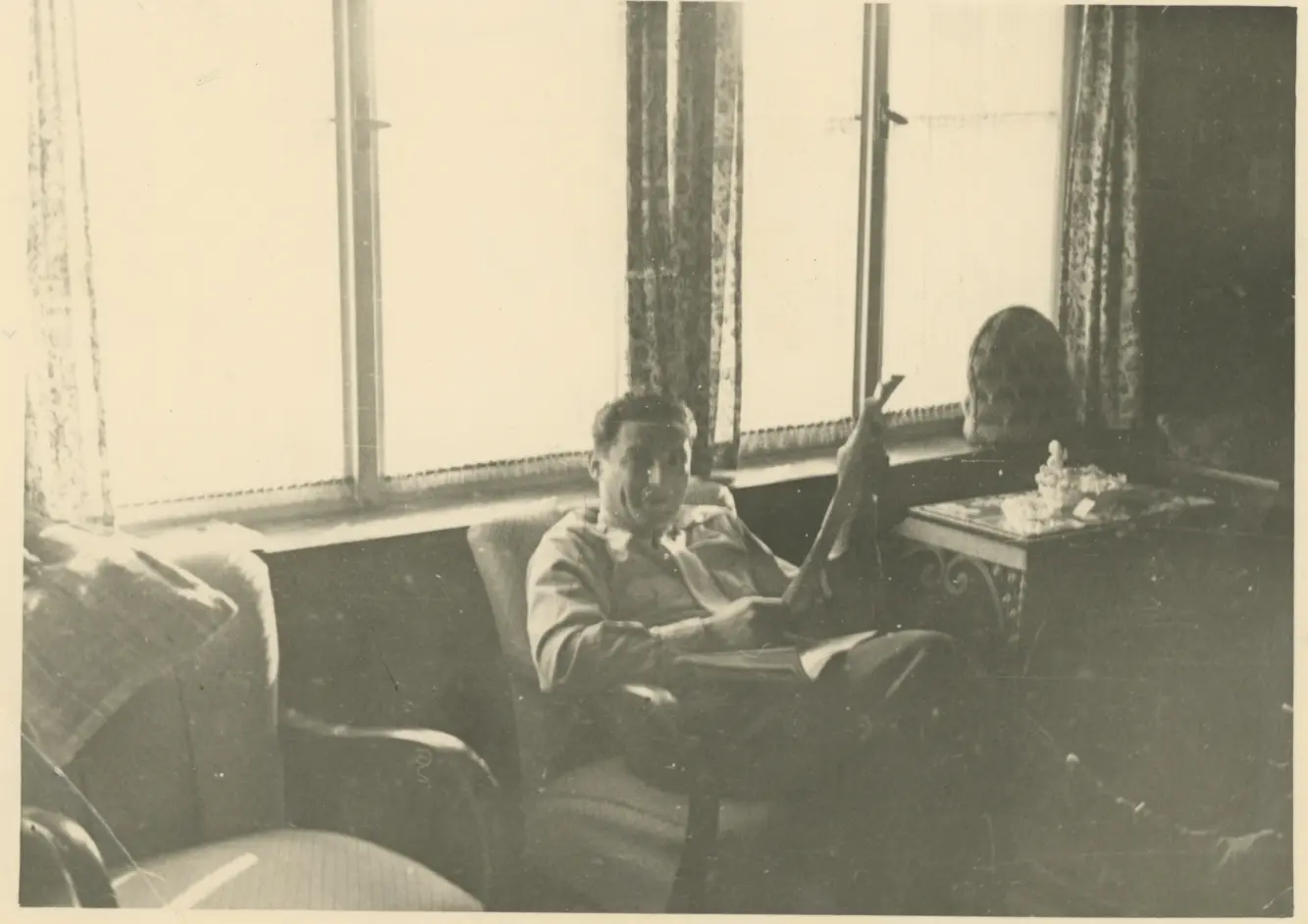

Peter’s brother in an American military uniform in the former Flossenbürg concentration camp in May 1945.

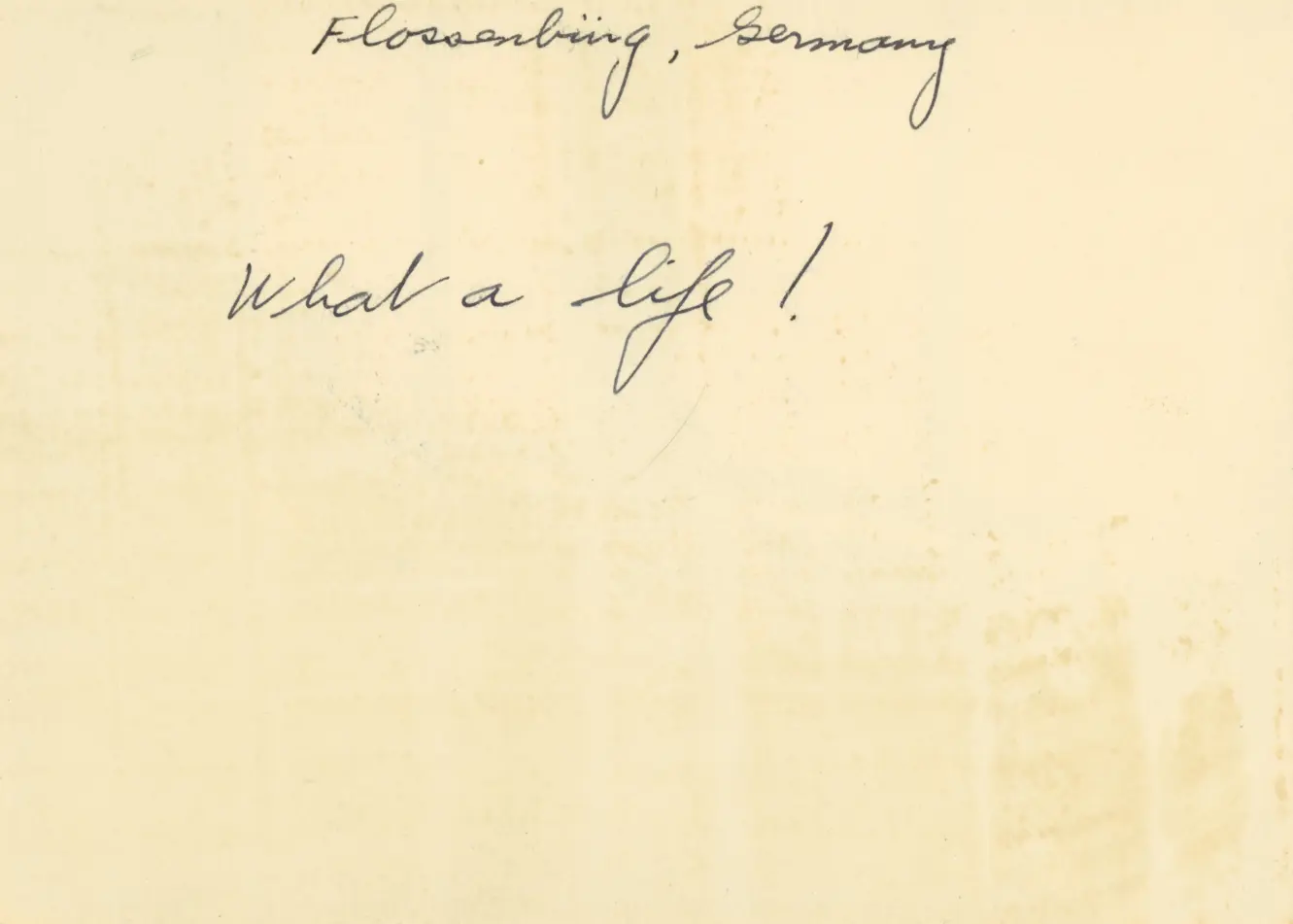

Peter’s brother, dressed in an American Army uniform and smiling, is sitting in a well-furnished room at the Flossenbürg concentration camp. The back of the picture reads “What a life!”

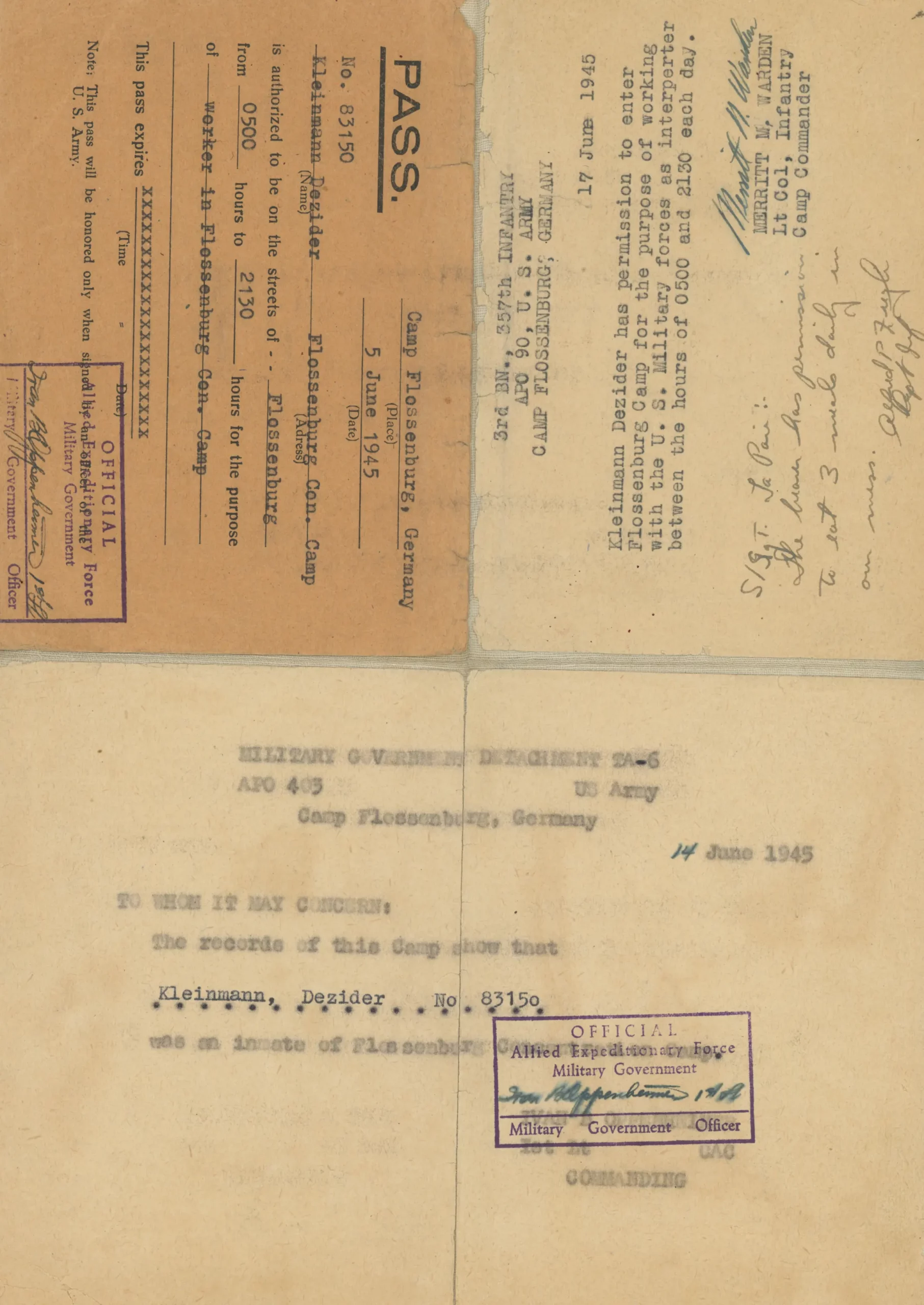

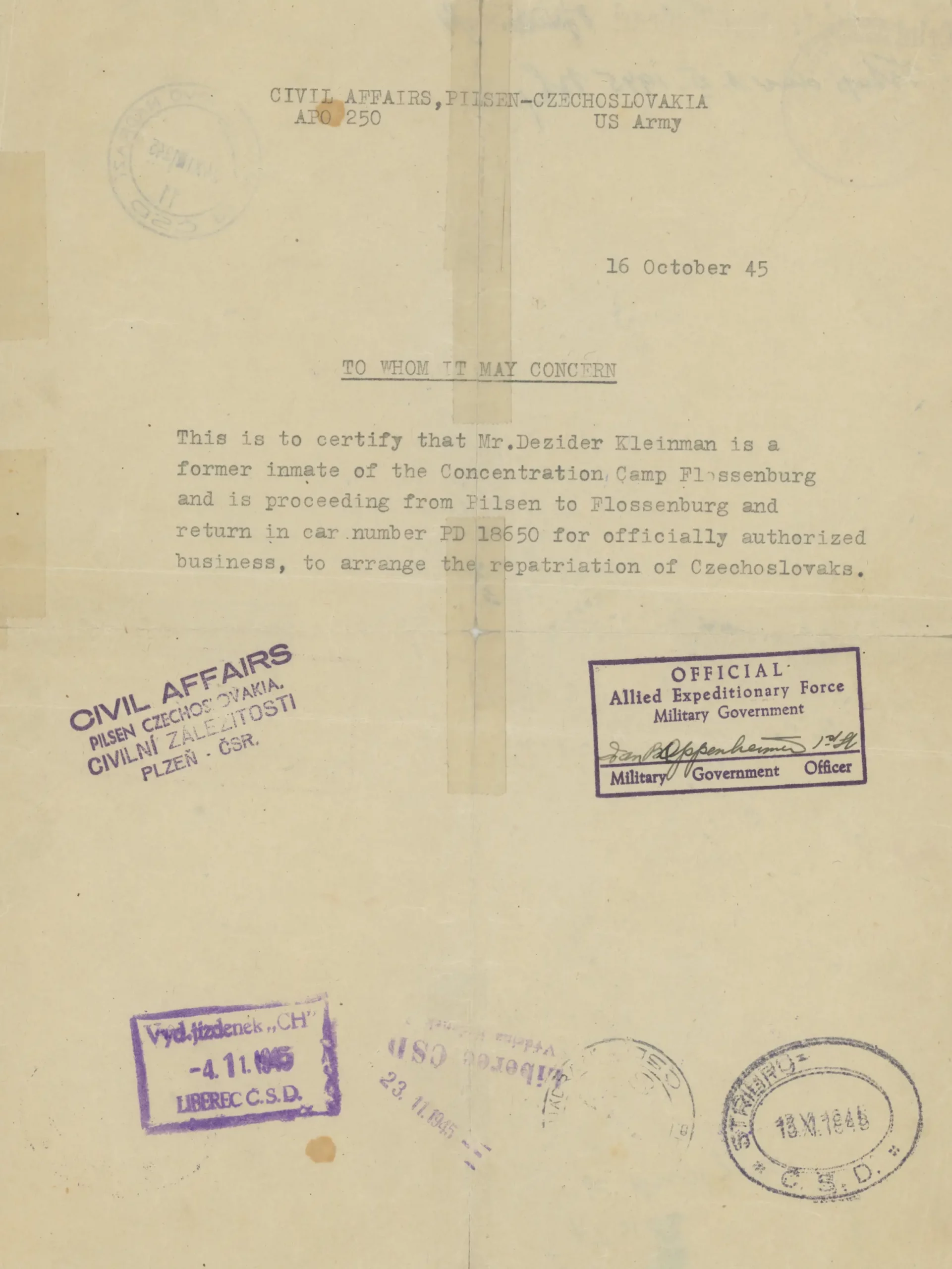

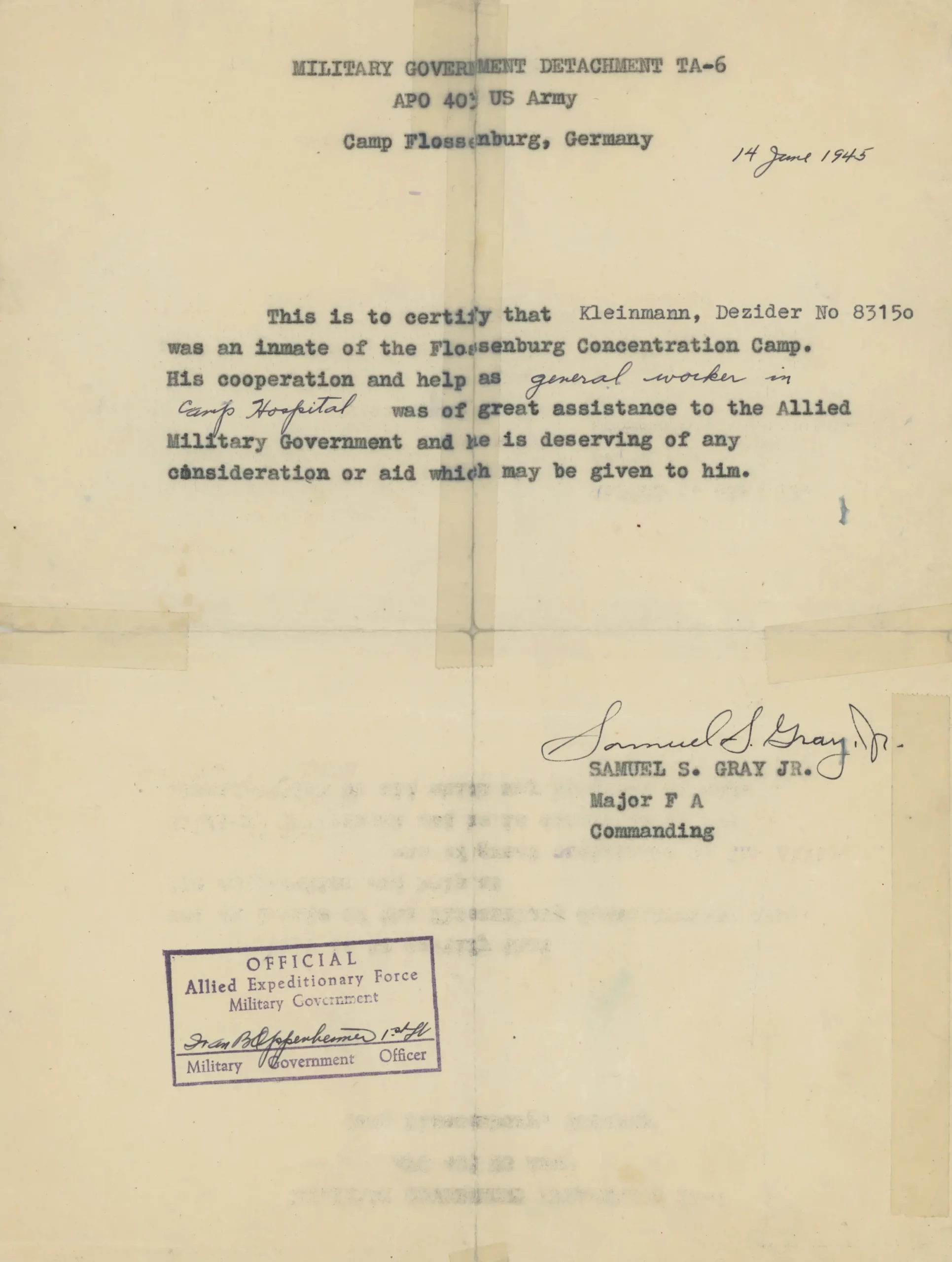

These documents were issued to Dezider Kleinmann from the U.S. Military. They allowed Peter to be in the village of Flossenbürg from 5 AM to 9:30 PM so he could work with the U.S. Military forces as interpreter in the former Concentration Camp. The document at the bottom certified his status as a former inmate of the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp assigned the number 83150.

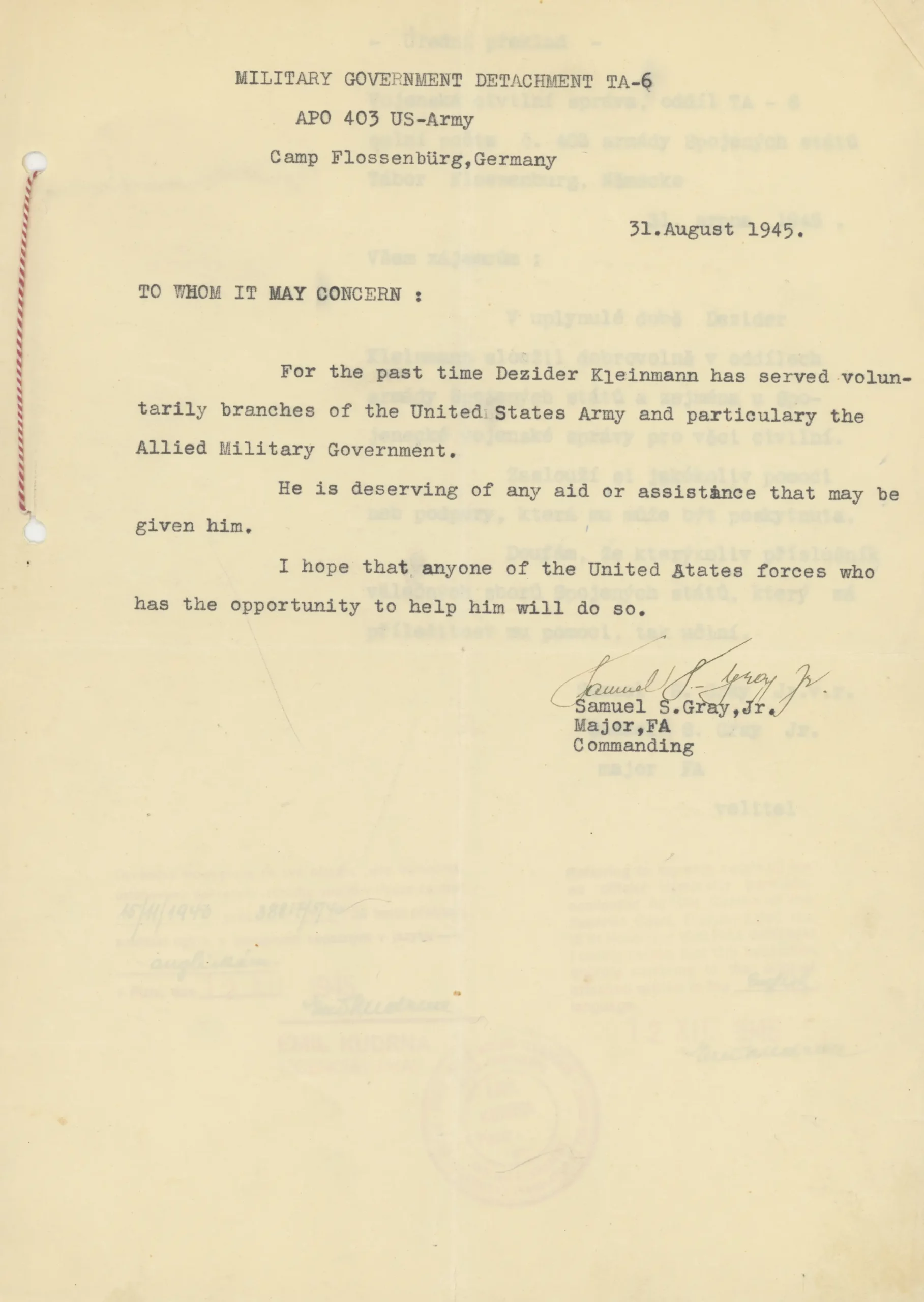

This document was issued on 31 August 1945 and signed by Major Samuel S. Gray, the liberator of Flossenürg. It states that Dezider Kleinmann is eligible for any help that the U.S. forces may provide him. On a second page the document was translated into Czech.

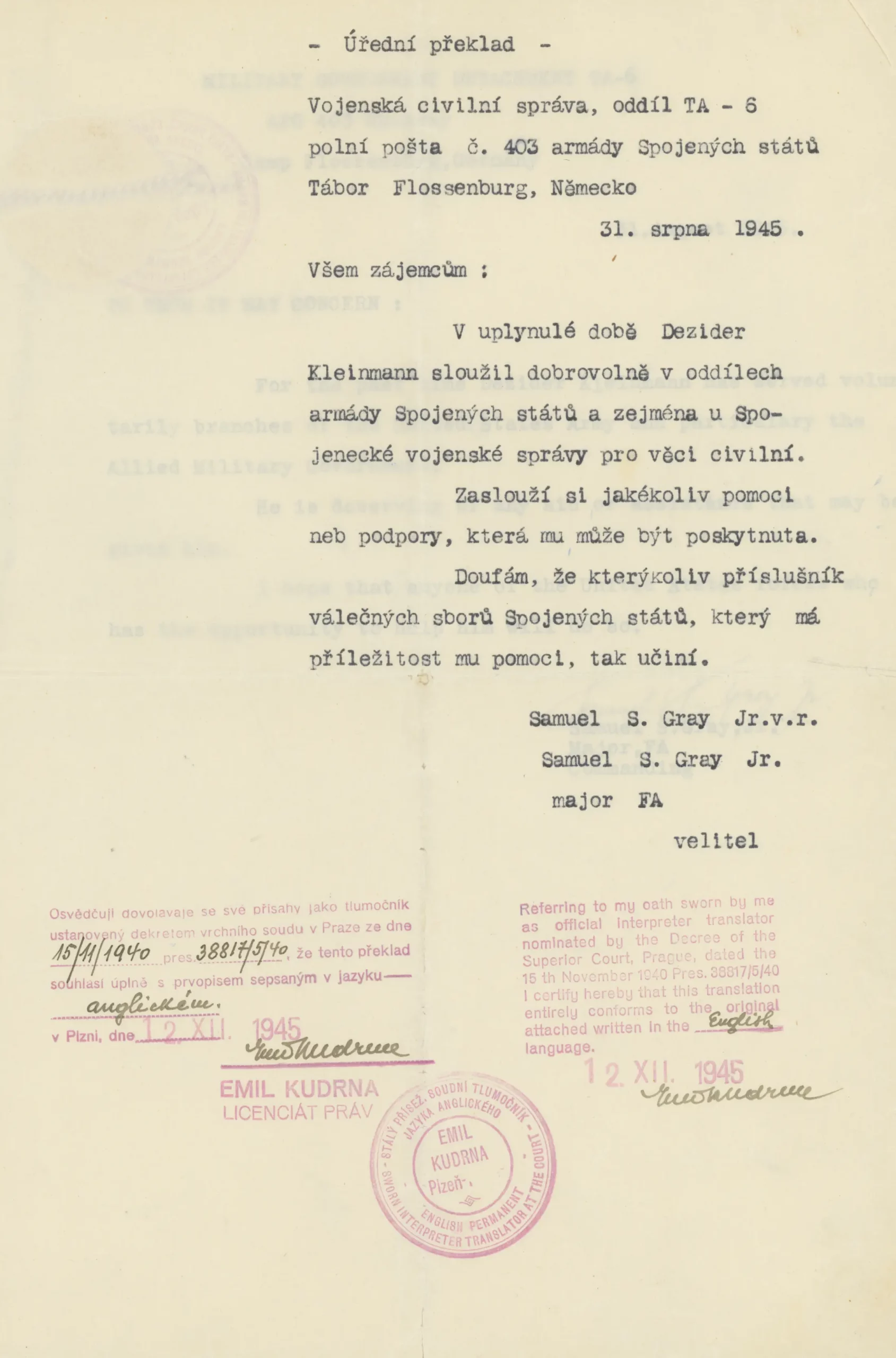

This letter of recommendation is from U.S. Lieutenant Warden N. Merritt concerning Peter and his brother called Adolph. It especially praises Adolph’s linguistic abilities but also confirms Peters upstanding character.

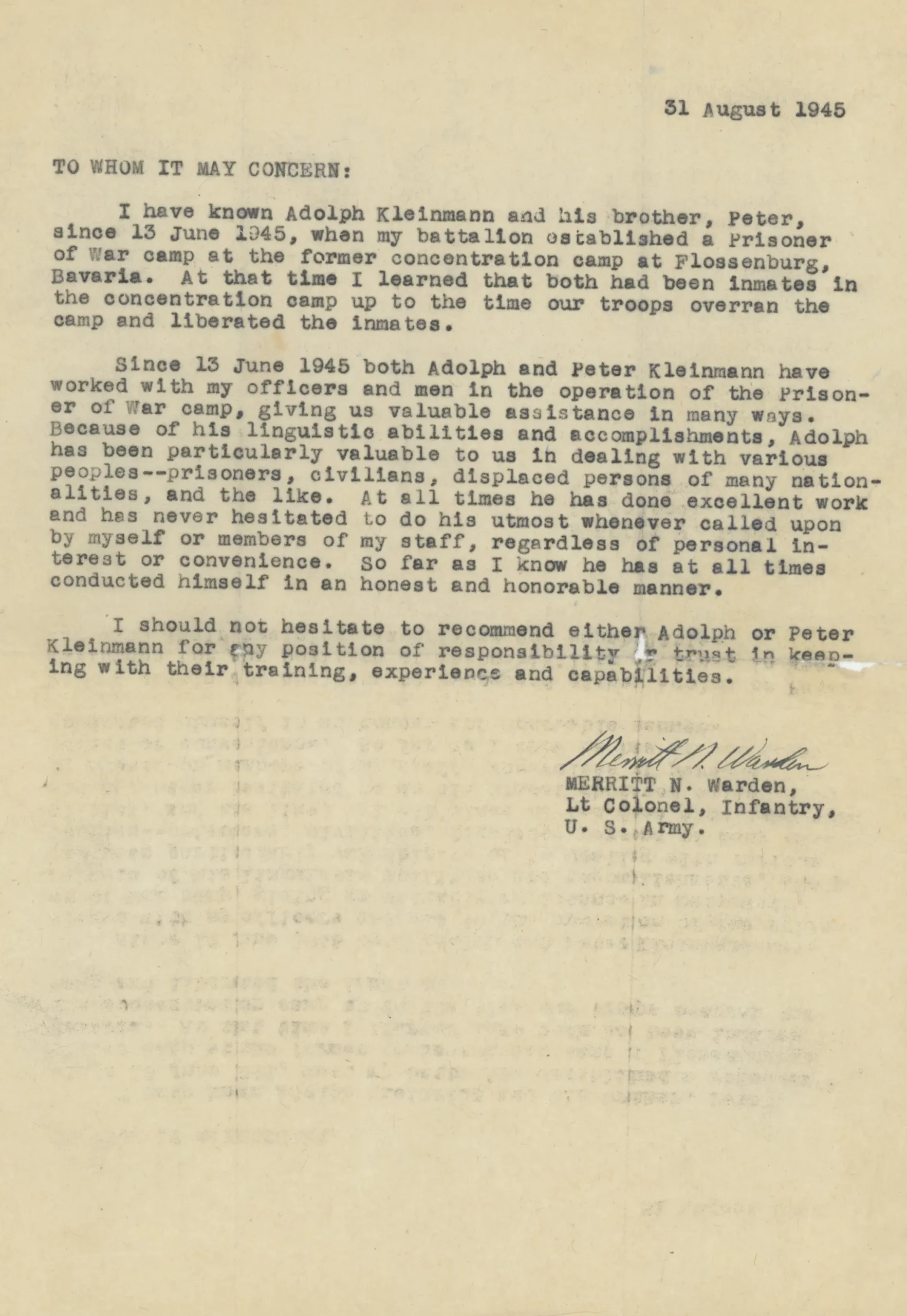

This document issued on 16 October 1945 confirms that Peter is a former inmate of the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp and that he is authorized to accompany the repatriation of Czechoslovaks from Flossenbürg to Pilsen, Czechoslovakia. It was signed by Lieutenant Ivan Oppenheimer.

This document dated 14 June 1945 and signed by Major Samuel S. Gray, the liberator of Flossenbürg confirms that Dezider Kleinmann has been an inmate at the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp and that his work in the Camp Hospital after liberation was very helpful to the American Military forces.

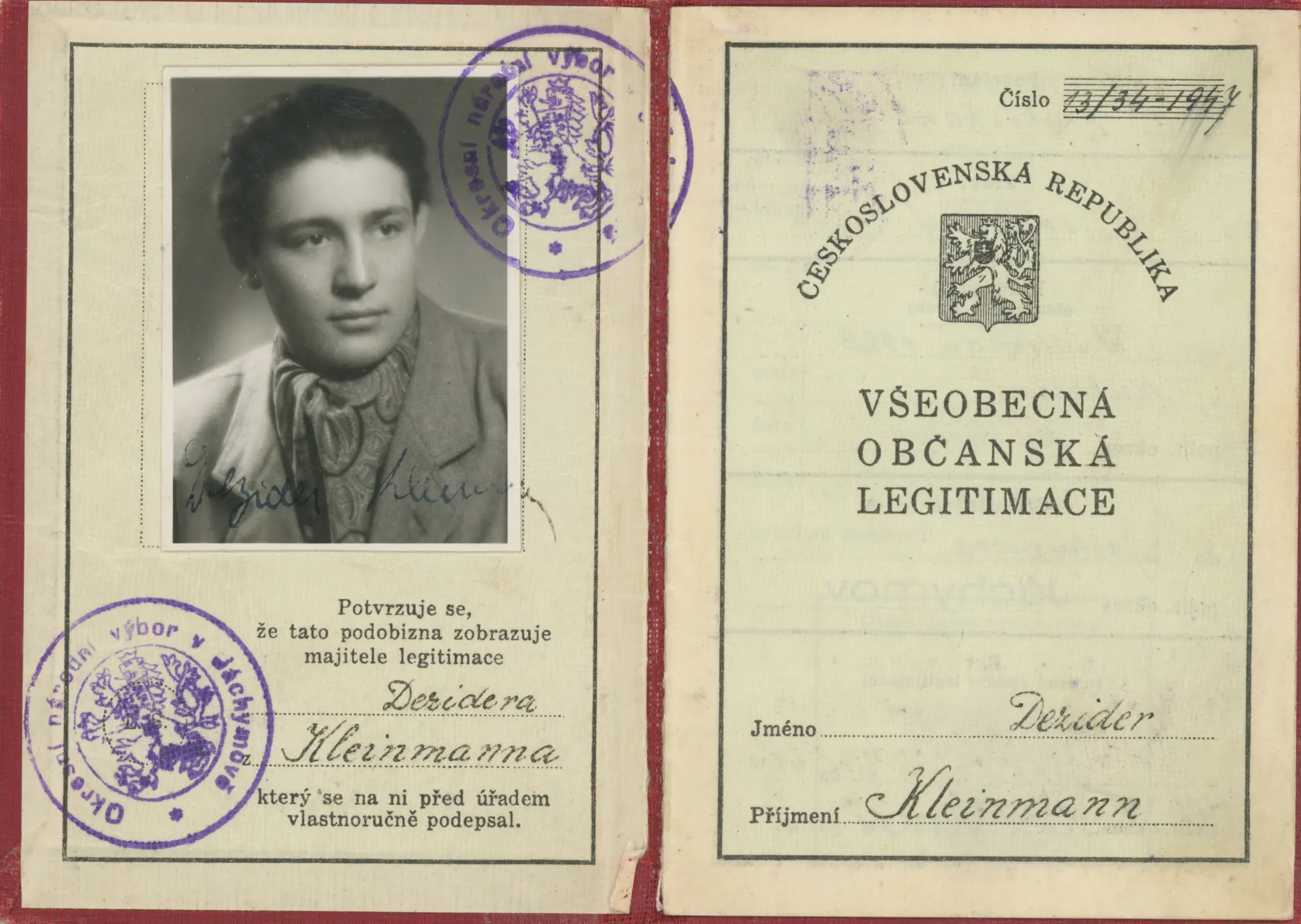

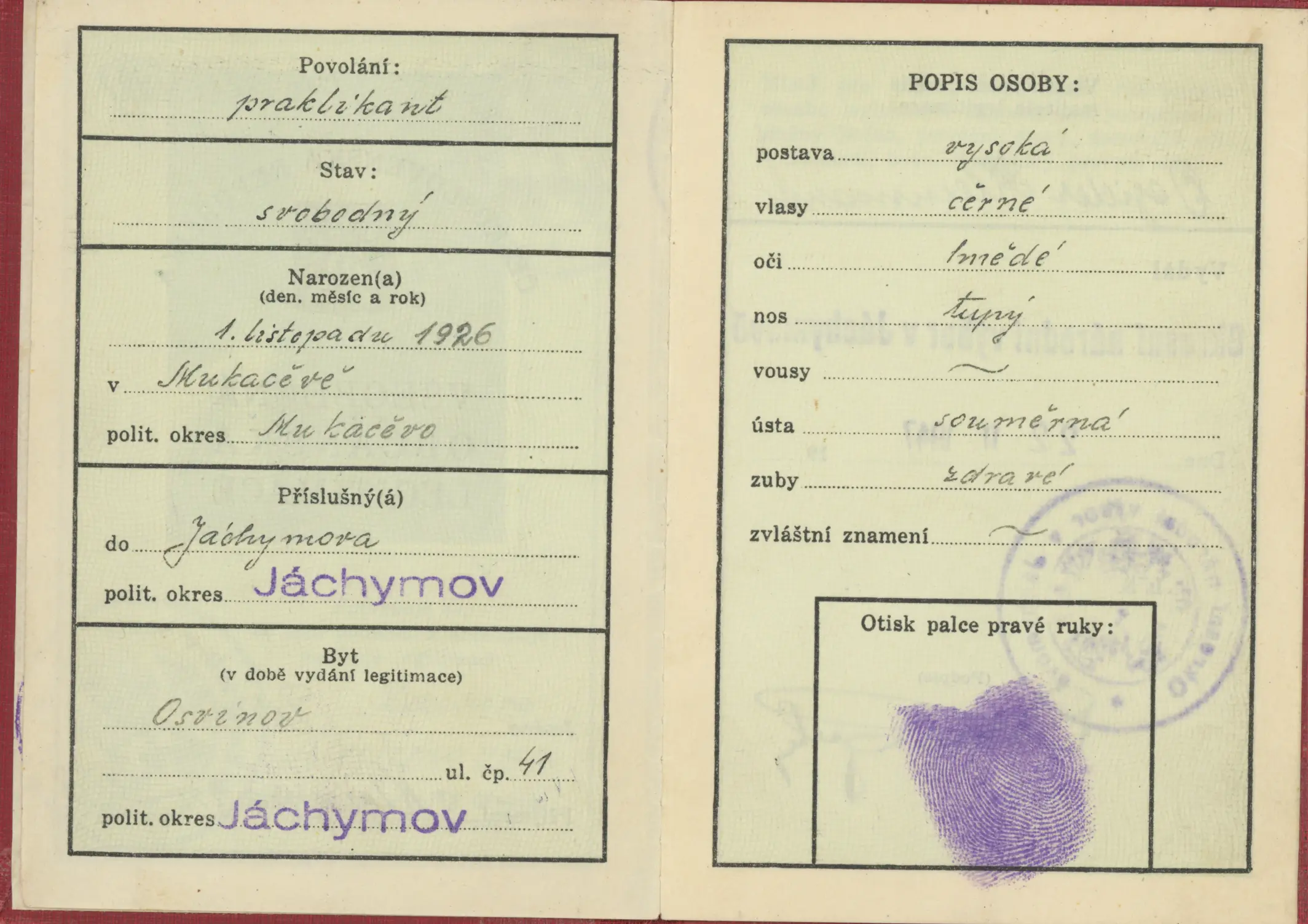

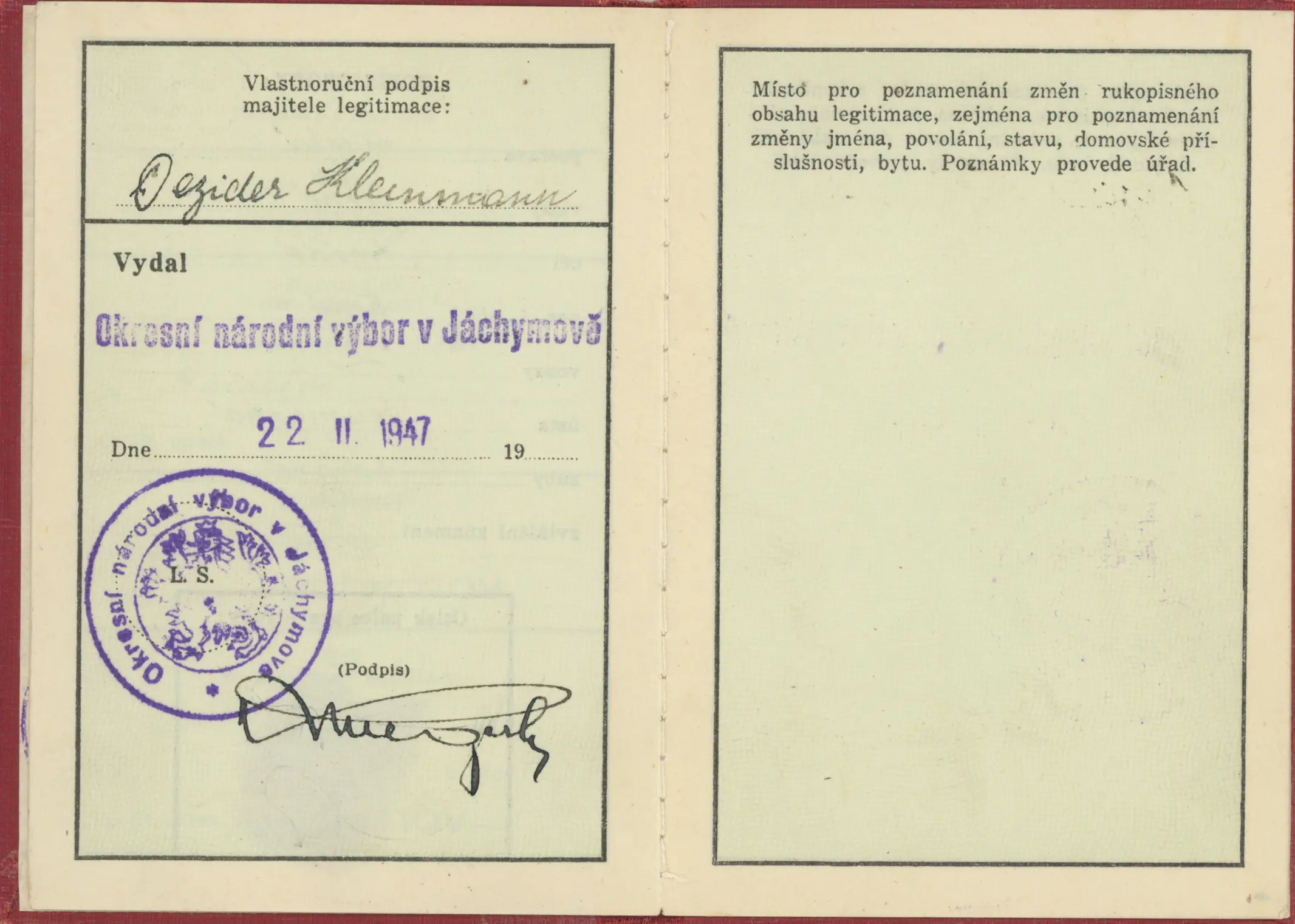

Peter used this document to avoid military service after the Soviet occupation of Munkács.

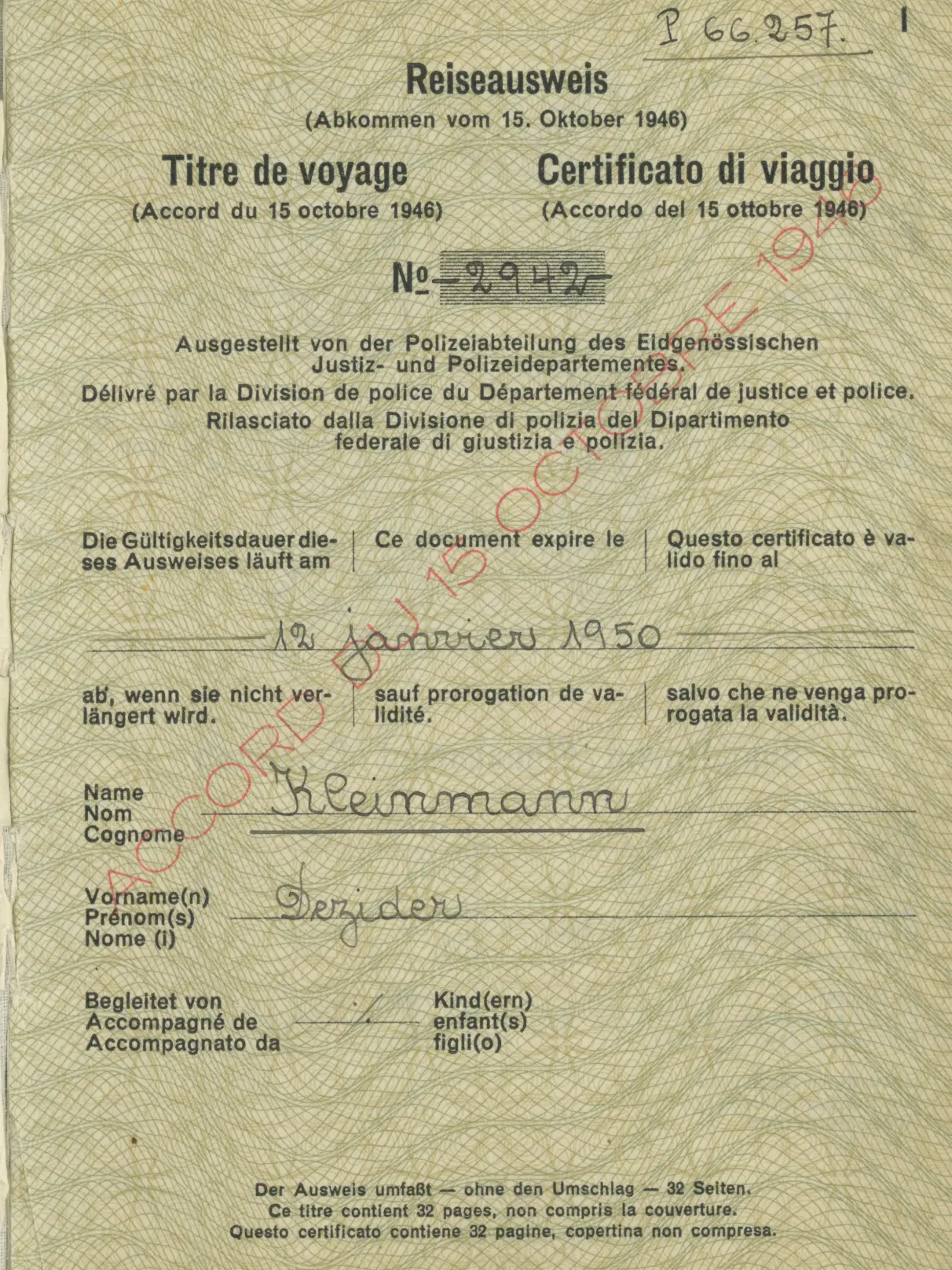

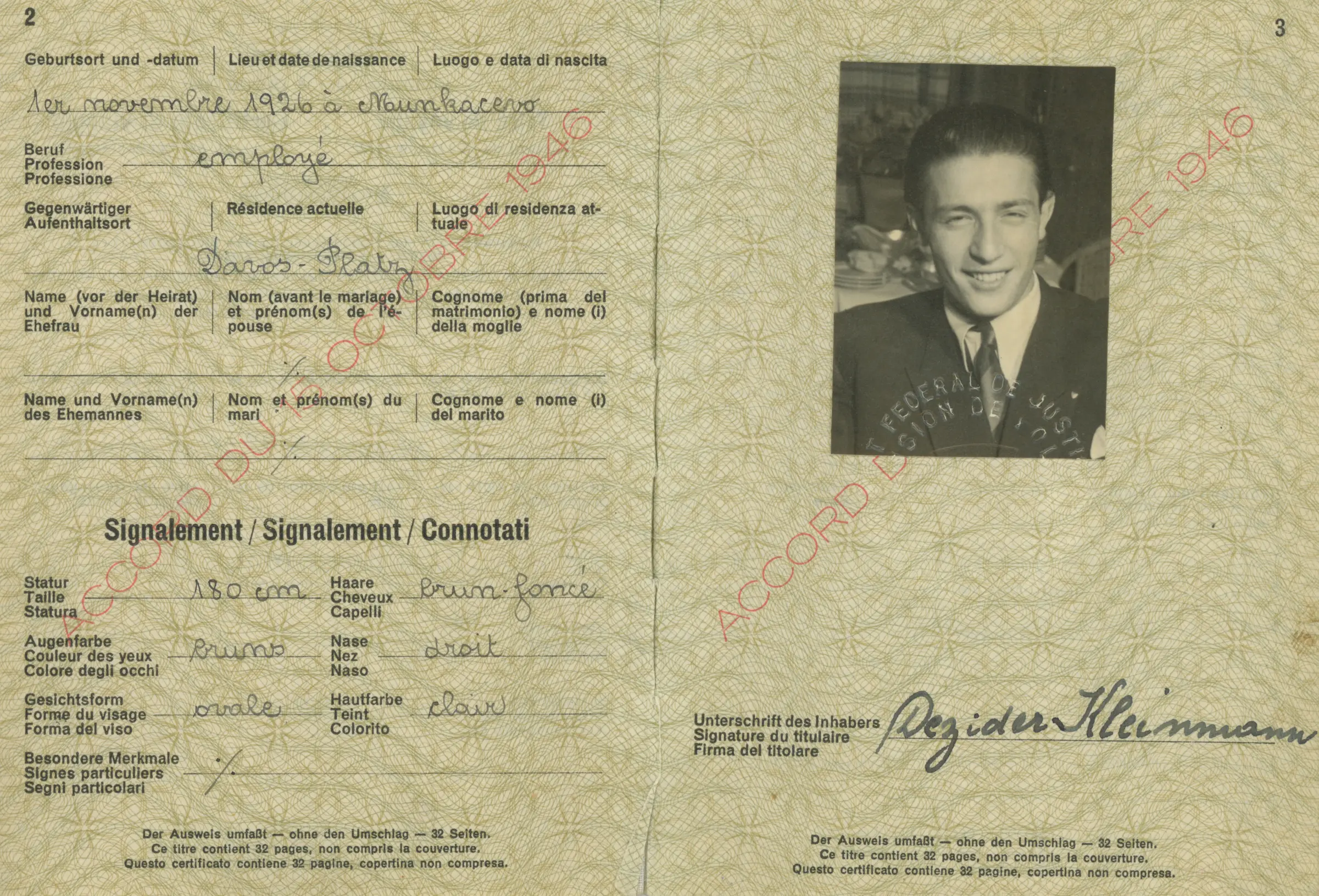

After the war the Russians had occupied the Carpathian region. Peter did not want to live under their rule. He was soon to be 20 and concerned that he would be required to serve in the Czechoslovakian army. His citizenship was debatable, for over the past five years, the hamlet where he was born had been part of Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Germany, and was soon to be Russian. He feared that there might be a pact between the Russian and Czech governments, and he would be sent back to Munkács. Military service was compulsory for men of 20. The army at best could be postponed for only a year. Returning to Munkács was not an option for Peter. Lieutenant Oppenheimer said he should buy the testimony of two witnesses who would say that he was born in 1926. With this extra year Peter could plan how to leave eastern Europe. That’s the reason why this document says Peter was born in Kustanovice on 1 November 1926.

This birth certificate issued by the Soviet government in 1990 indicates Peter’s true birthday, which is 1 November 1925.

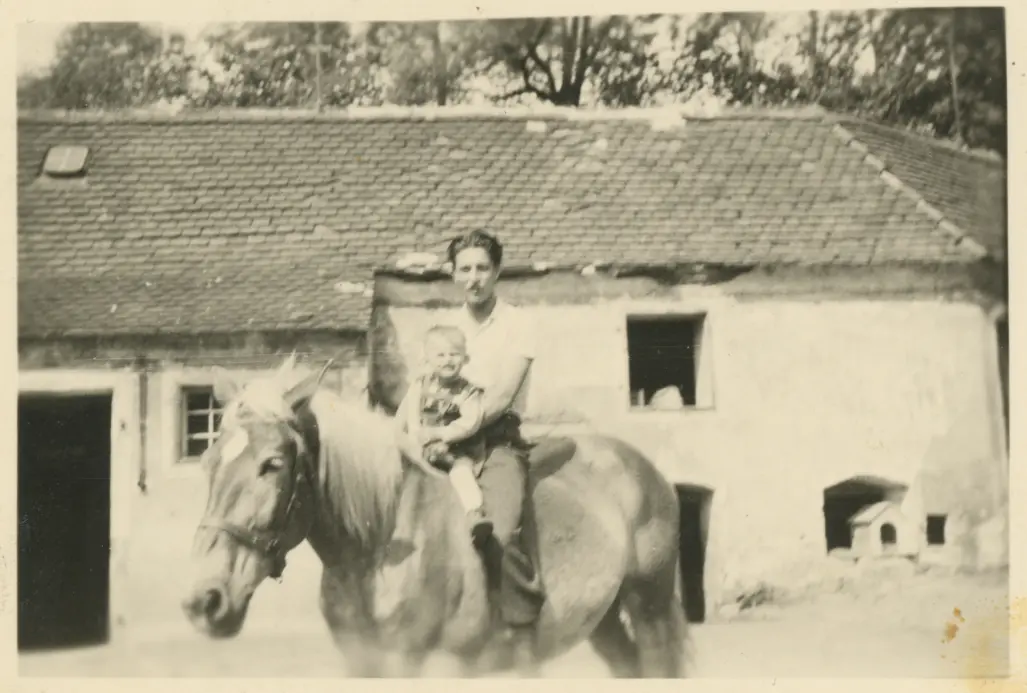

Peter on a farm in Ostionoff, Czechoslovakia in August 1945.

In August 1945, Peter and his brother were given a farm by the Czech government in Ostionoff near Karlovy Vary in Sudetenland. There was a sawmill, as well as chickens, cows, geese, horses, and pigs, and a large garden. In the winter the horses were used to draw logs from the forest. University students worked on the farms as part of a work programme initiated by the government.

Peter (first picture: standing, second picture: sitting on the very right side) partying with other patients of the Schatzalp Sanatorium in 1948.

In 1946 Peter was diagnosed with tuberculosis. At the time, total rest in sanatoriums was the prescribed treatment for those suffering from tuberculosis. So, his brother inquired and made the necessary arrangements for him to recuperate in the Schatzalp Sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland. Peter stayed there for two years before emigrating to Canada.

Peter (standing in the middle) with other patients in front of the Schatzalp Sanatorium.

This picture is another example of Peter’s new life in Davos.

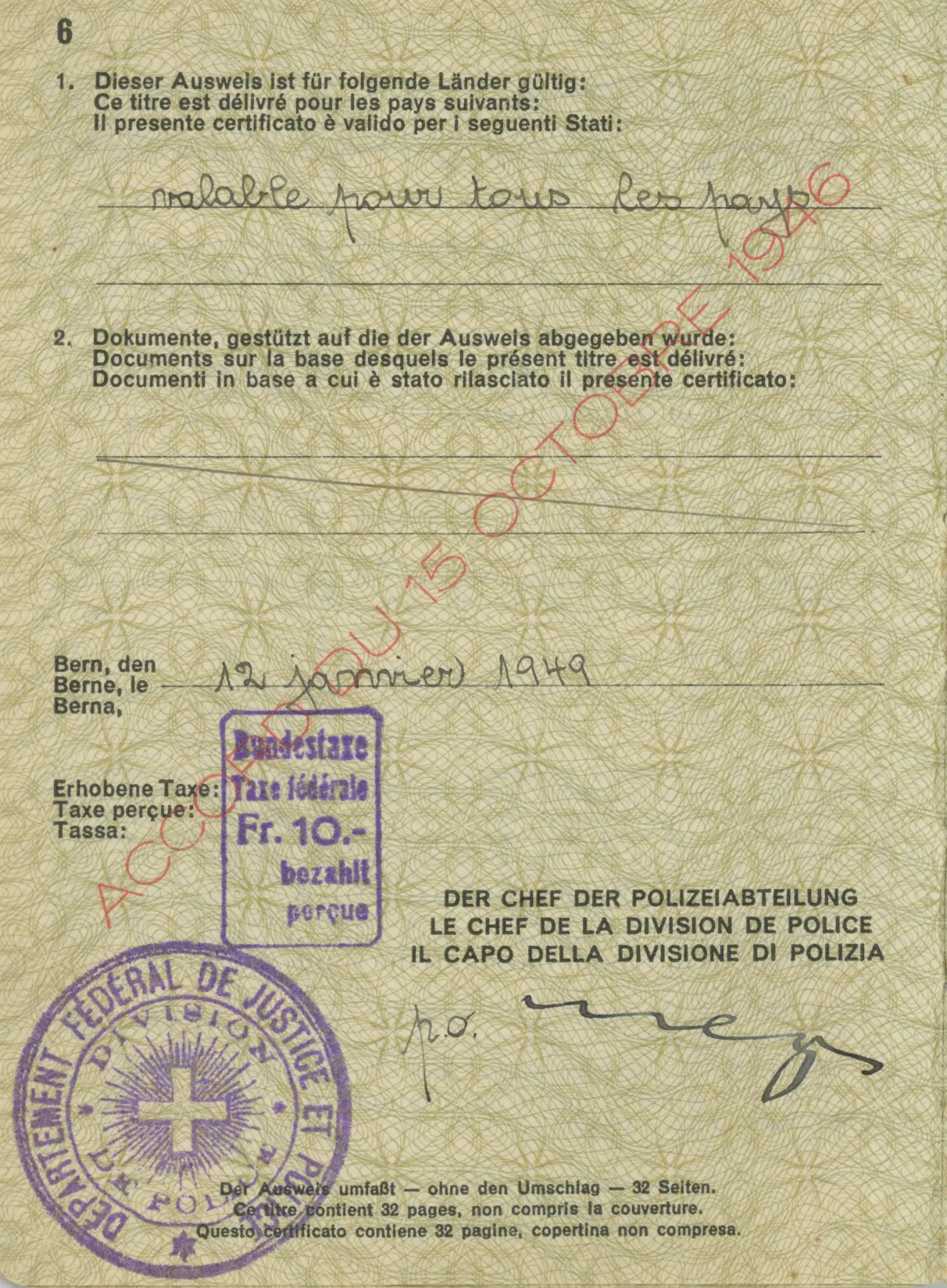

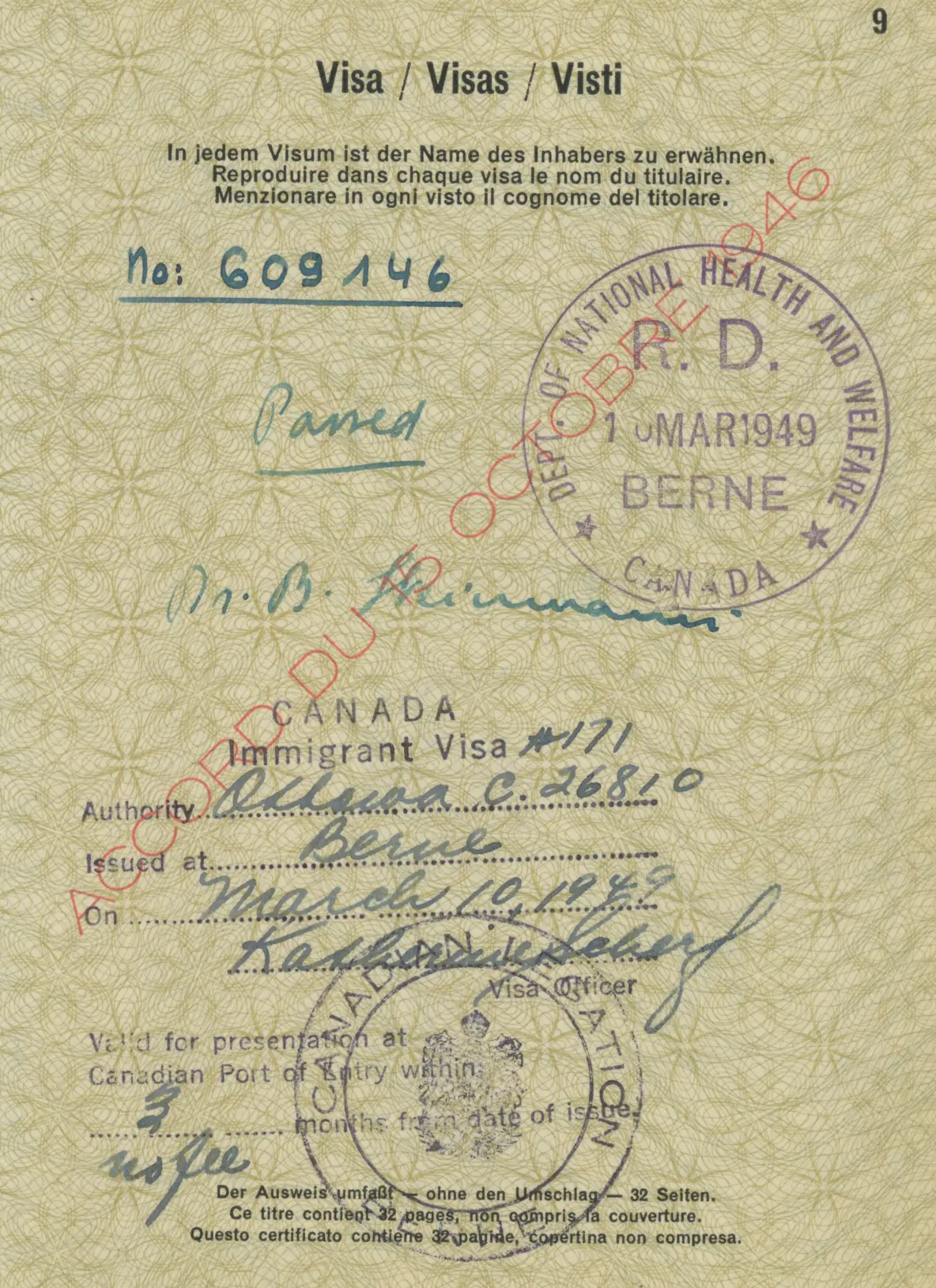

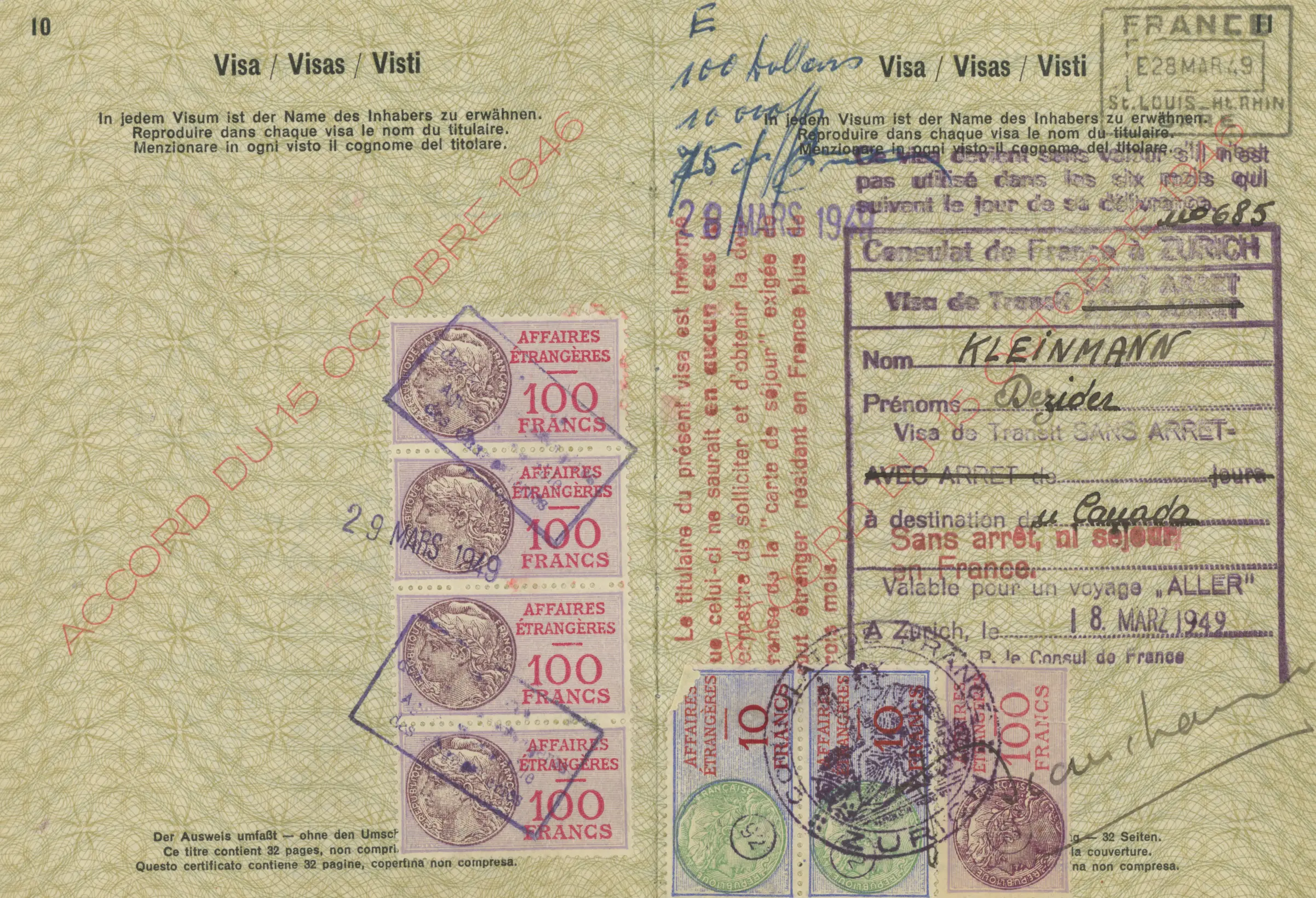

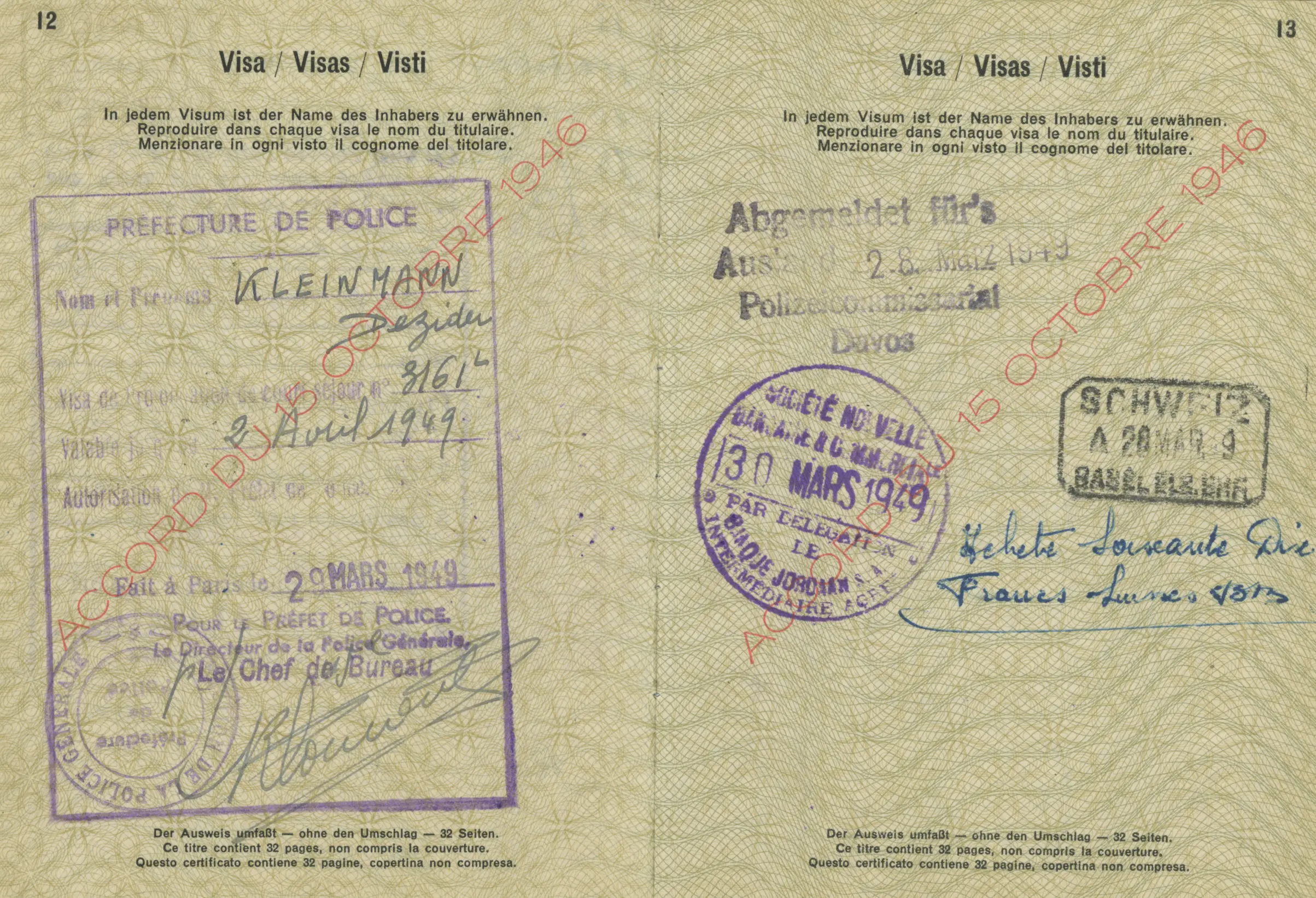

This is a Swiss passport issued to Dezider Kleinmann on 15 March 1946. This passport also contains Peter’s visas for France and Canada issued between the end of March and the beginning of April 1949. From the port of Le Havre, France, Peter travelled six days on the SS Scythia. He arrived at pier 51 in the port of Halifax, Nova Scotia on 13 April 1949, which is also registered in the passport. From there he immediately travelled by train to Montreal, Quebec.

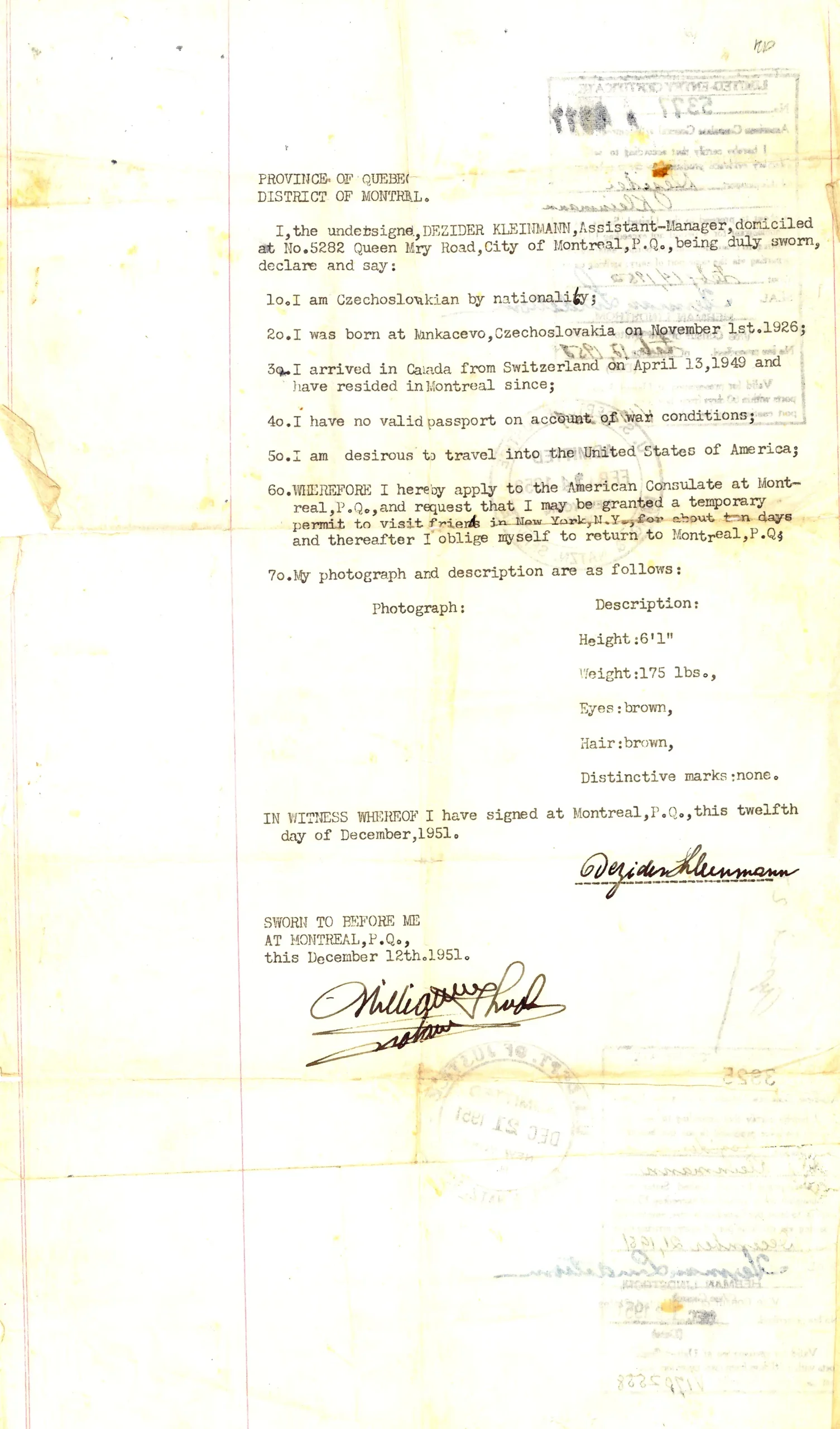

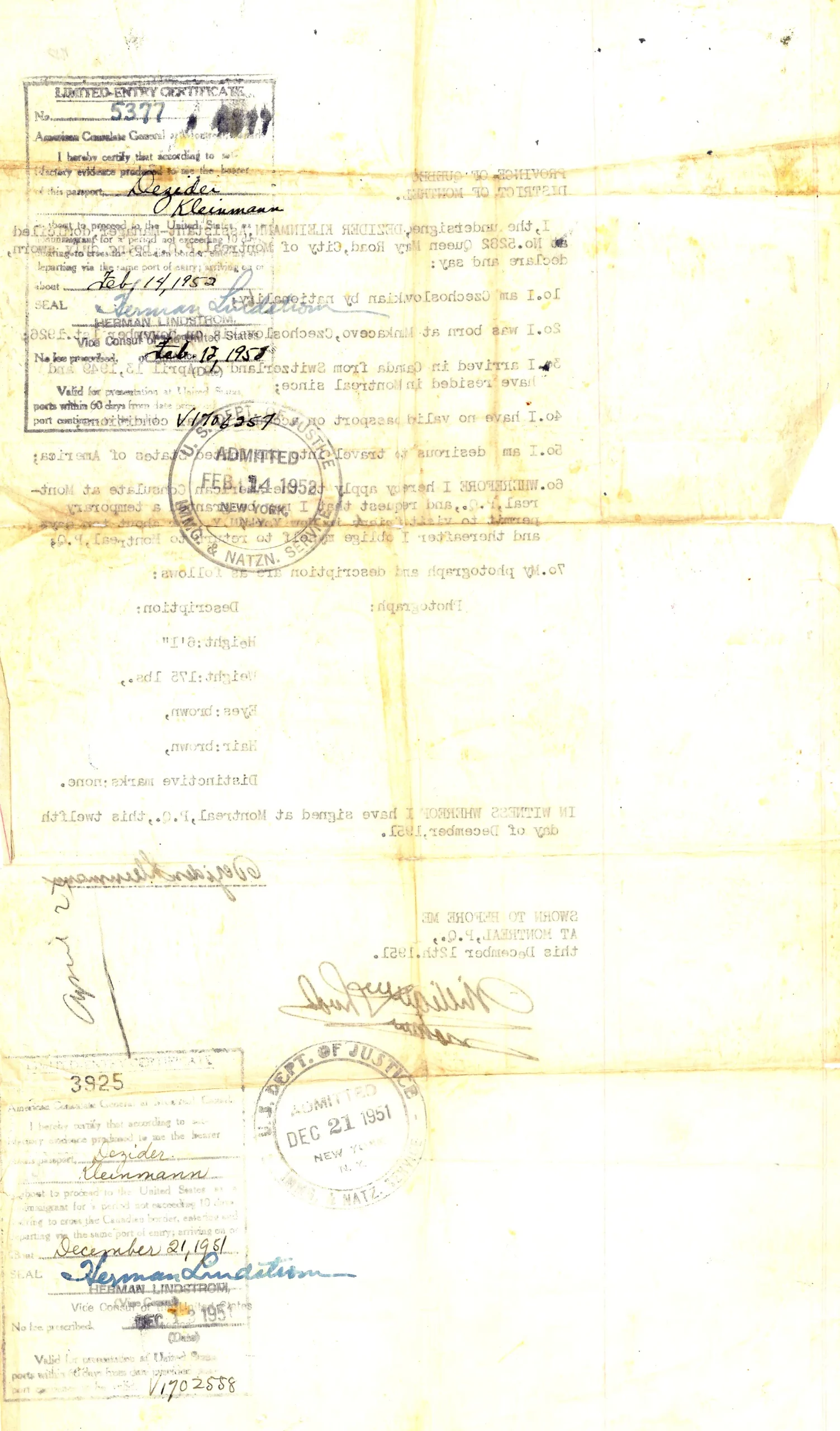

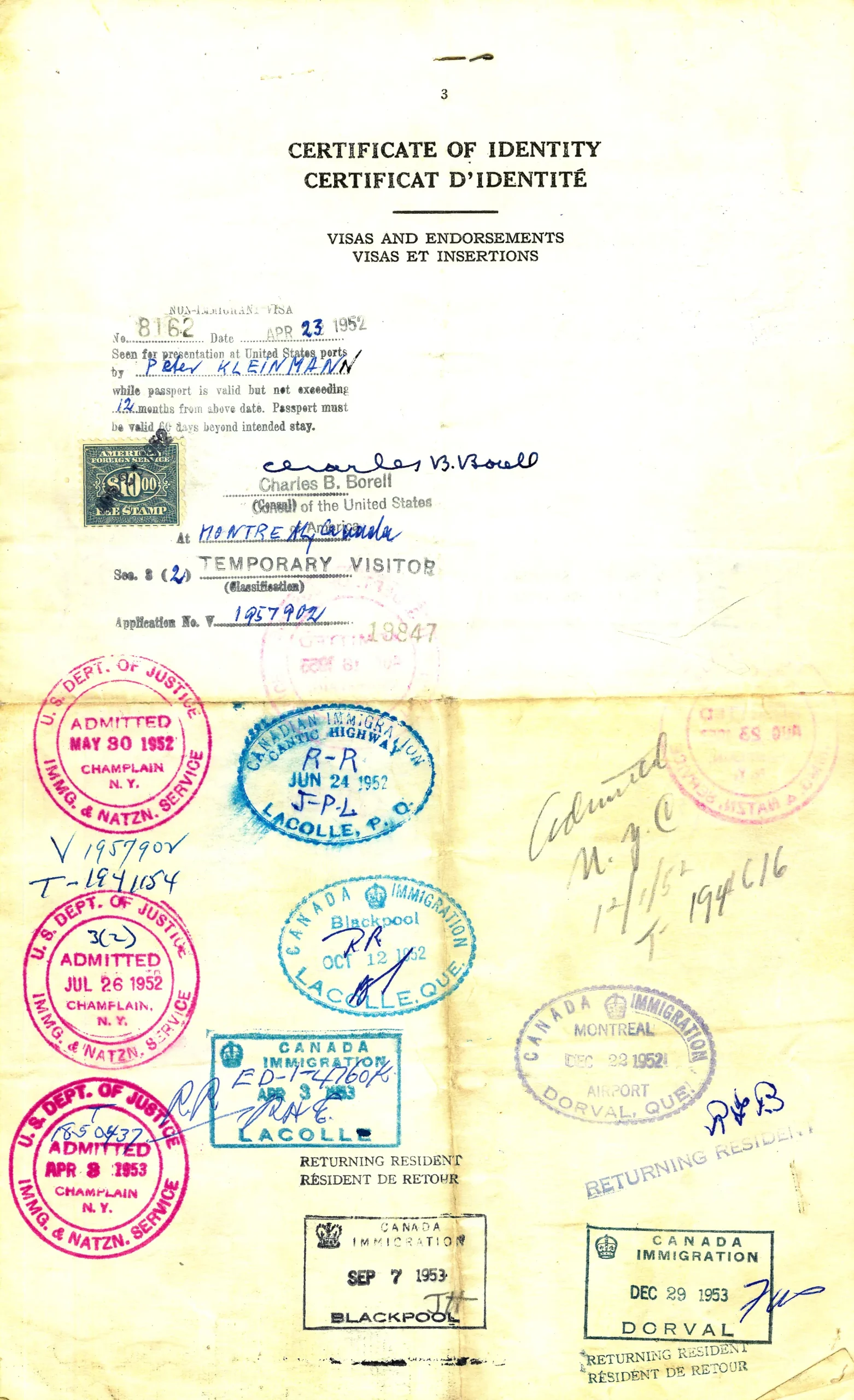

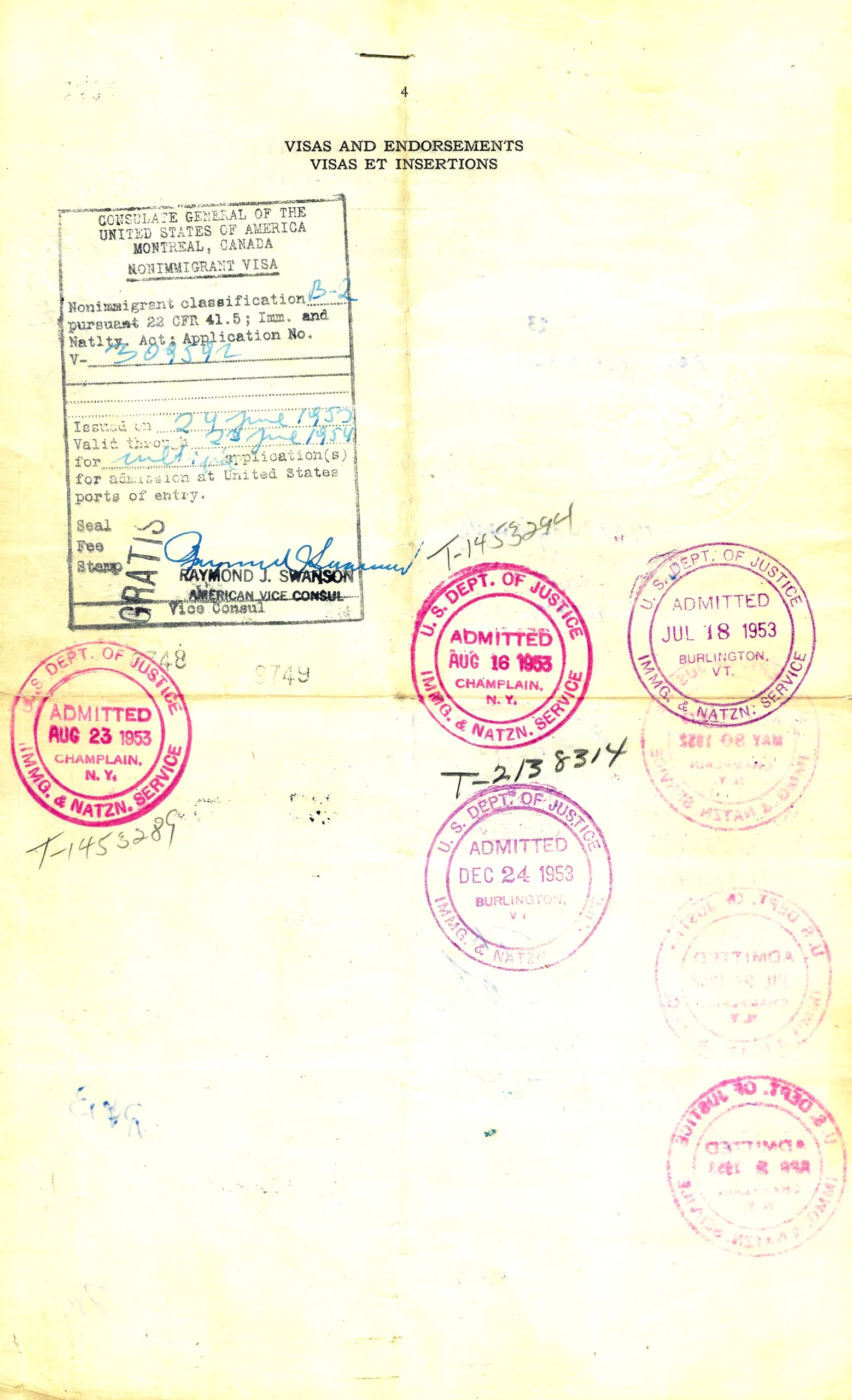

By the time this document was issued on 12 December 1951 Peter was living in Montreal. He applied for a permit to travel to New York to visit friends. This application states that Peter had sworn that he was a Czechoslovakian born in Munkacevo, Czechoslovakia on 1 November 1926 who arrived in Canada from Switzerland on 13 April 1949. As one of Peter’s previous passports this certificate of identity indicates the wrong date of birth since Peter was actually born on 1 November 1925.

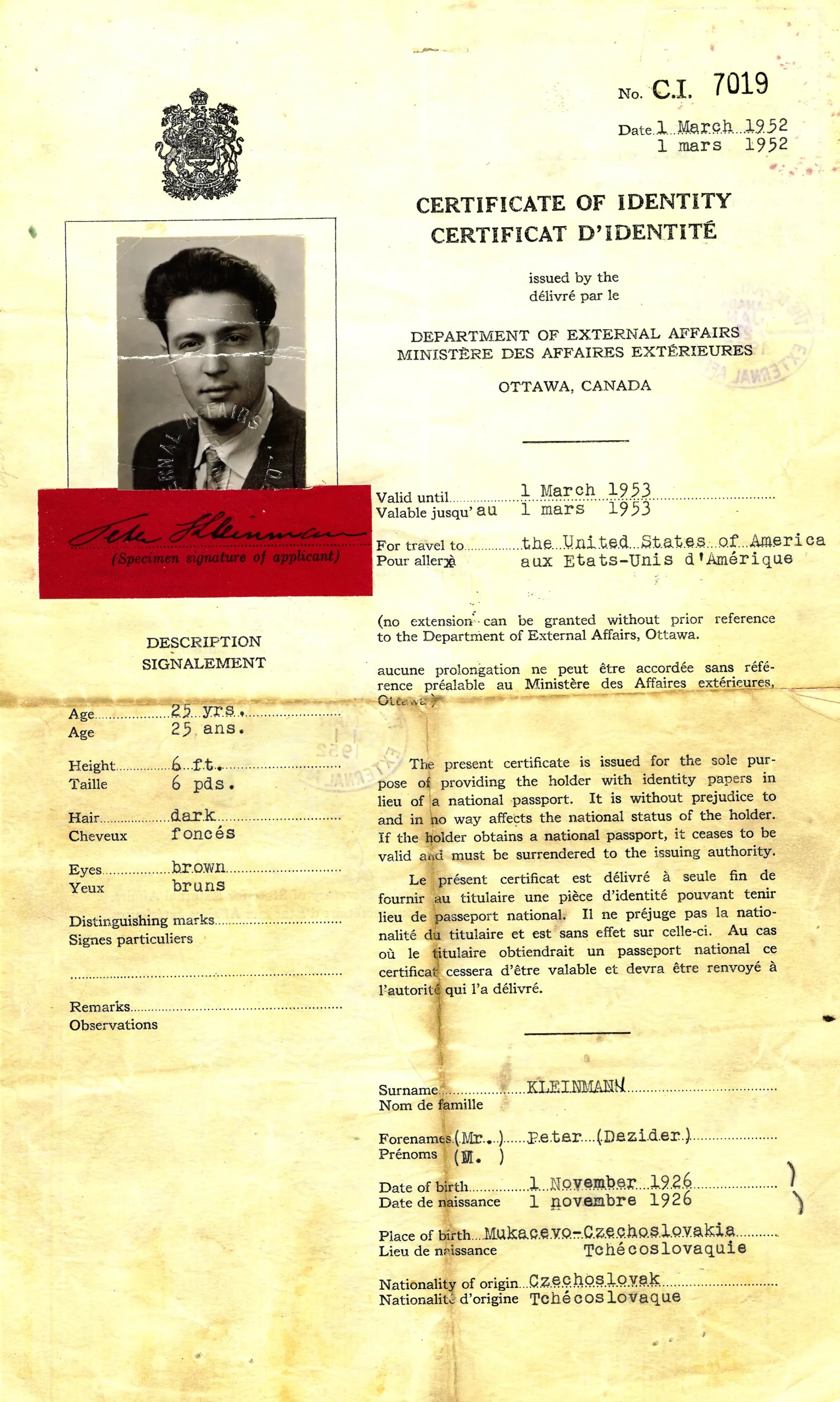

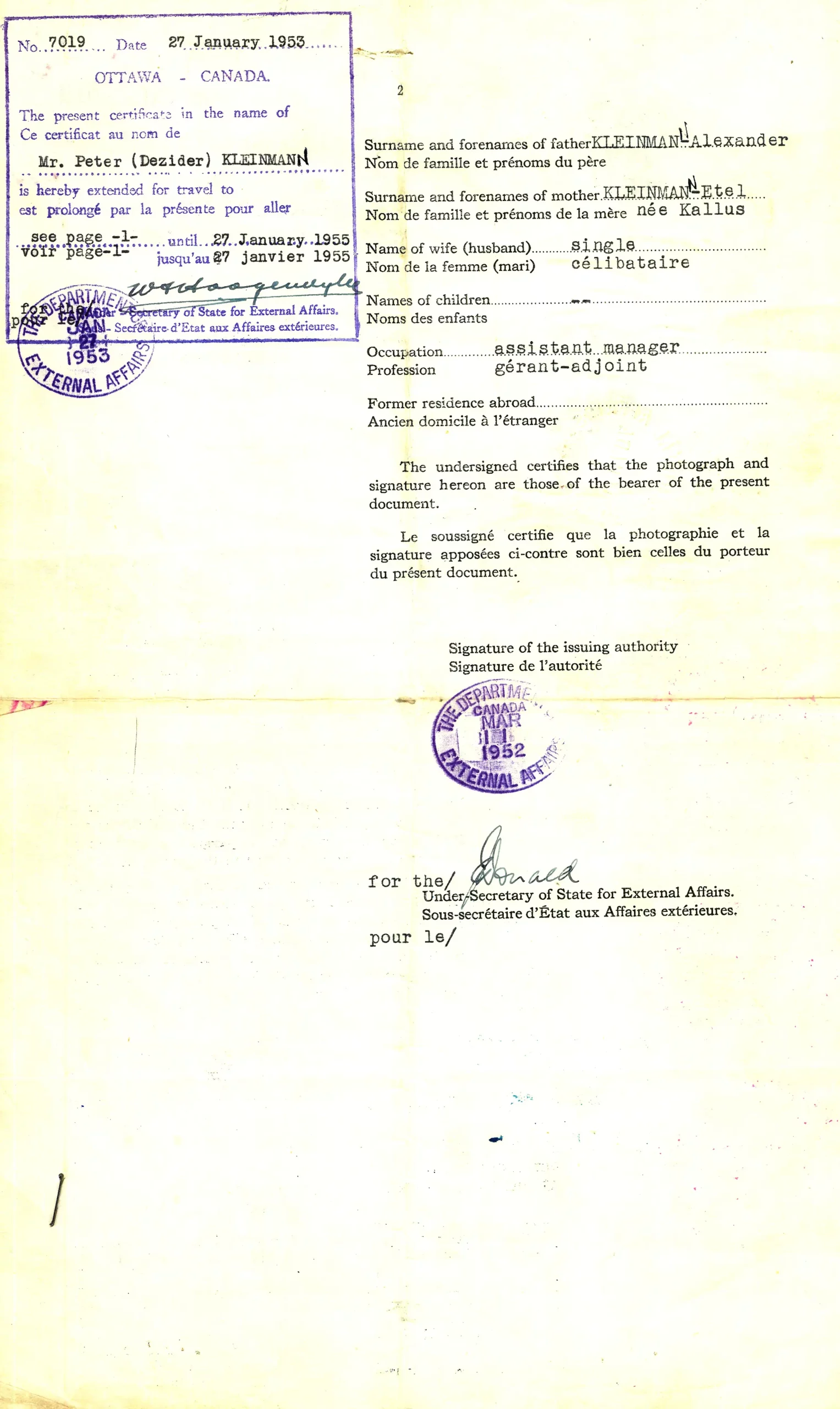

This Certificate dated 1 March 1952 and issued by the Department of External Affairs in Ottawa allowed Peter to travel to the United States. Peter is described as a 25-year-old assistant manager who is six feet tall, has dark hair and brown eyes. This document, like the application, includes the wrong date of birth which is 1 November 1926 although it should be 1 November 1925.